Full Archive

A complete archive of every post, unsorted.

What a drag it is getting old.

I wonder if becoming a curmudgeon is an inevitability for the opinionated and pretentious. The true meaning of the word pretentious in particular. I feel that the word’s usage has transformed into “snobbish” or “stuck up” rather than one who pretends to be substantial.

While I do not particularly loathe all things new, I must confess a confusion with what becomes favored among younger audiences. In some cases this is a clear generational gap, such as that between my niece and me. It can also be as short a span as five-to-ten years difference with my… younger peers, I suppose they’d be? A question of whether I’ve grown out of touch simply by being born a few years earlier.

While I’m not afraid the things I love will vanish, there is an apprehension towards what the future may bring. I’d like to think I’m open to change, but at the end of the day I imagine all creatures fear the complete loss of their comfort zone.

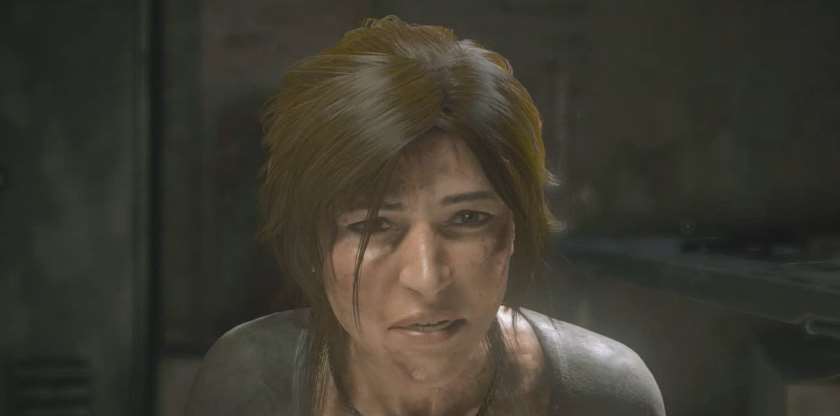

Shadow of the Tomb Raider wants to make a statement. Shadow of the Tomb Raider makes its statement very poorly.

Leading up to release I was under the impression that Shadow of the Tomb Raider was intended to be a criticism of white colonialism. The developers were very clear early that Lara Croft would be the one to cause the Mayan apocalypse. The message received was that it was not her intentions but her arrogance that would lead to such grave consequences.

Swiftly the story moves into the legendary city of Paititi, a Mayan civilization untouched by and hidden from the modern world. There is a superficial reverence for the culture, trying to depict the attire and mannerisms of the indigenous peoples as accurately as possible. The game seems intent on making the player understand that the ancient Mayans weren’t “the savages” that cultural stereotypes might assume.

Then Lara violates the Prime Directive to “save” a little girl from being made a blood sacrifice at the hand of her father – an act the daughter professes to be an honor. The mother, in the meantime, is completely accepting of the murder of her husband by Lara’s hand so that her child may be saved from the ritual.

All of the improvements in climbing are a bit wasted on this iteration of Tomb Raider, but could lead to a potentially fresh new chapter for Lara Croft in the future.

Despite its many combat woes, Shadow of the Tomb Raider still manages to provide a rich world littered with hidden caverns and secrets. While the franchise as a whole has suffered a bad habit of just dropping ancient scrolls and relics on the ground for any passerby to pick up, the devoted explorer will still have plenty of hidden gems and artifacts to seek out more intently.

Nevertheless, the designers seemed to only partially comprehend the draw of such exploration. A number of tombs and caverns are only accessible once you’ve accepted the relevant side quest from a local. It does not matter that you know where to go or have all the necessary tools required to access the cavern. The game will either place an artificial obstacle in your way until the quest is accepted, or removes any relevant tool prompts until an objective marker hovers over the offending blockade.

Side quests were largely unnecessary in Rise of the Tomb Raider, but they never interfered with the player exploring at their own pace.

Are Patriotic Christians confusing their allegiances? Or do they simply not see how their views compromise their duties as both Christians and Americans?

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof;

It may have been seven or eight years ago when I finally realized how strange it was to be singing America the Beautiful during a Church service. I can only imagine it was a byproduct of Post-WWII America that Patriotism and Faith became intertwined, fueling false notions of each founding father being a Christian and forging this nation with the intent of being God’s Country.

There are certainly Christian founding fathers, and a multitude of other historical figures that certainly believed in Christ the sacrificial son of God. However, it is very clear that the founding fathers never intended America to be a theocracy. Before even the freedom of speech or the press are guaranteed, the First Amendment ensures its citizens that never shall the government establish an official religion, nor should any religion be banned.

Yet the Patriotic Church-Goers have tongues tied with accusations of their country being invaded by sinful filth, wrecking America’s good Christian nature. While the history books are already filled with the sinful realities of America’s bloody, prejudiced history, I will not be dwelling on such lessons of fact. I merely wish to focus on the tragedy that these Patriots hail allegiance to a government that demanded they compromise from day one.

Chris and Steve are getting fatigued a lot lately. This time by the prevalence of skill trees, especially in games where they prove unnecessary.

Whaddaya mean yer not done yet?!

"Whaddaya mean yer not done yet?!"

So I’ve clearly not met my self-imposed deadline of releasing a video in October. As of this writing, I’ve not even finished the script for it.

I wish I could say with certainty that it will be out in November, but at this point I do not wish to make any further promises. As I’ve noted in the past, I do not make exclusively videos. I enjoy writing essays for this website, and I think without them I would actually go a bit nutty. This means a lot of my time spent on writing is spent on writing other things. What hasn’t particularly helped this month are the amount of games I’ve also been playing, as well as the erratic and unsteady state of my mental health.

I’ve certainly become sodden with guilt for this lengthy creation of the video. For many reasons I’ve focused my attention on playing a variety of games in October, not all of which were necessary to complete within the span of the month. In fact, there was no proper deadline for any of them. I am actually certain to have Game Log content until December at this rate. So why not focus on what’s more important?

A consideration on how my shifting thoughts on replayability are changing my playing habits.

I don’t really keep up with what metrics are used to determine a game score these days. Despite writing about games constantly, I keep up with very little games writing in the greater world. I read headlines that catch my eye or the odd post from a friend here and there, but unless your name is Shamus Young then I’m not really keeping up with your work.

To that end, I don’t know if a game’s “replayability” remains a factor in its final score. When I was younger, this notion of “replayability” was meant to capture how enjoyable a game was to return to once the credits rolled. It’s an understandable metric when you consider the arcade origin of games, but even by the Super Nintendo it was becoming an oddly subjective variable that could only be determined by a series of factors.

While it’s been a long time coming, this past year has driven me to truly question the way we value this “replayability”. I touched on some of these revelations back in February in regards to my approach to discussing and analyzing games. The latest catalyst of change, however, was a return to Destiny 2.

Shadow of the Tomb Raider's additions to stealth could have made it a far more enjoyable game than its predecessors... too bad it's too often too poorly implemented.

I don’t think Eidos Montreal had the best grasp of what made Nu-Raider work.

...what? Don’t ever use that phrase again? I mean, I thought it was clever, and… okay, okay! I won’t write or say it ever again! Cripes…

I stand by my point of Eidos Montreal’s slack, slippery grasp of the new Tomb Raider games, however. While I wouldn’t say either game is exceptional, there is a heart to those titles that could have been something phenomenal. I think half of Shadow of the Tomb Raider manages to tease us with what could be, but the end product is tarnished with the everything that no one was asking for. This week I’ll be focusing on the combat, where it excels, and where it disappoints.

Bad Times at the El Royale has more than a few similarities with Cabin in the Woods in this way, but it also allows Goddard to write a story that is wholly his. Humorously enough, it turns out a story that is wholly his also feels like a Quentin Tarantino film, only with a bit less blood and complete absence of the heinous N-Word.

A strange game. The only winning move is not to play.

The El Royale hotel sits smack dab on the divide between California and Nevada. On the side of California is a bar stocked with liquor and alcohol while on the other side gambling machines reside. An establishment built upon a gimmick of each state’s advantages and disadvantages, all reliant upon which side of the border you happen to be on at that very moment.

It’s also a very blunt signal to the viewer that this film is about to explore some form of duality.

The film begs another question, however: just how significant is the difference between these two sides? How fine is the line? Or is it all just a game?

I should warn that I can only give a surface level reading of these concepts. I’ve only seen the film once in theaters and plan to more thoroughly explore it with subsequent viewings when it releases on Blu-Ray. Nevertheless, consider this write-up to be a first impression rather than a thorough analysis. A voicing of theories as opposed to firm arguments.

I haven't had this much fun with a Mega Man game since the Super Nintendo.

I’m not sure I can call myself a proper fan of Mega Man. I hold no dislike for the games, and in fact enjoyed any I had managed to play. There was some sort of magic to combatting the robot masters in the appropriate sequence, inflicting the weaponry of their comrades against them. However, I also missed out on the discovery of this sequence by relying on Nintendo Power to clue me into the best order to approach each stage.

Which left me with having to master each game’s obstacle courses. Having to learn to time jumps while fending off hordes of enemies was never my favorite activity, ultimately leading me to throw the controller into the ground. I owned Mega Man 6, but for all that I played it I rarely beat it. I couldn’t stand the difficulty of Wily’s – pardon, I mean “Mr. X’s” – castle due to its increased obstacle course difficulty.

On the other hand, Mega Man X became one of my most beloved games of all time. I preferred the more action-oriented approach over the tricky obstacle courses of the NES games, and the levels hid secrets more akin to The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past and Super Metroid than its own predecessors. Gathering health boosts, rechargeable energy tanks, and pieces of armor were a lot more satisfying to me than 1-Ups and E-Tanks. In fact, any attempt at a 1-Up or an E-Tank in the prior games could result in the loss of a life itself!

The Sunday Studies column returns not with a renewed sense of purpose or direction, but a revelation of all-encompassing fear of expression.

At the start of the summer I wrote part one and part two of what was meant to be a three-part series. I’ve read and enjoy the current draft for the final part, but I’m not entirely certain it conveys the lessons I’ve learned in the months following.

This series became an effort to explain my philosophy, but throughout I could not help but feel the pressure to defend myself. What is there to defend? Why am I so insistent that this conflict exists between believers and non? In re-reading my first essay I cringed as I carelessly referred to non-Christians as “sinners”.

Within a certain context there’s a logic to the term’s use. Those that believe are “cleansed” by the blood of Christ’s sacrifice. God forgives us of our sins so that we might become worthy to bask in his presence. However, just because a believer has forgiveness does not mean they are free of sin. If anything, sin becomes an even greater plague. Since I’ve increased my Biblical studies I’ve struggled more than ever before to be a better person. To be patient with others, to control what angers me, and to give up sinful habits and tendencies that would ultimately lead to negative behaviors and depression.

Your friendly neighborhood podcasters Chris and Steve come together to sling some syllables about Marvel's Spider-Man on PS4.

Sometimes it's enough just to find something that presses all the right buttons back.

It feels strange to confess that Darksiders might be one of my top ten favorite games of all time.

Keep in mind that I don’t have an actual ordered list in my possession or in mind. I have games that I consider to be foundational and games that I consider favorites, but I’ve never really bothered to sit down and create an official top ten. It just seems a bit absurd since the list will no doubt change as I get older. For example, ten years ago I might have put BioShock on that list. Enough time now has passed that I’m not so certain of its place. In fact, the only reason it’s a consideration at all is the prestige.

When it released, BioShock was a major touchstone of how AAA games could deliver a more literary story. It was the first time many players got to experience a meta-narrative in particular, the game acting as commentary to its own limitation of player freedom. Those familiar with System Shock may have found it “simplified” and lacking a “proper inventory”, but for console players like myself it was a major shift forward in Western games narrative.

Darksiders, on the other hand, was labeled as derivative. The choice description from the press was “a Zelda for grown-ups”. Taking the puzzling dungeon design of Nintendo’s Hyrule-spelunking adventure franchise and pairing it with the simplified combos of God of War and Devil May Cry, Vigil Games released a product that seemed to get a lot of heat for its lack of originality.

Despite all this, Darksiders is most assuredly one of my favorite games of all time.

Marvel's Spider-Man tries to tackle the webslinger's most recognizable slogan from different angles.

Warning: This essay will contain spoilers for the villains and ending of Marvel’s Spider-Man on PS4.

It seems every time someone takes their turn making a new Spider-Man story, they have to lean heavily into that theme of great power and great responsibility. Seeing as Insomniac chose to make their Peter Parker an eight year veteran of web-slinging through New York, it wouldn’t quite do to have him learn this particular lesson. Instead, they chose to tackle this concept in three separate ways. Focusing on characters that were corrupted by the great power they’ve been given, by teaching Peter he doesn’t have to shoulder the responsibility on his own, and forcing him to test his conviction in how committed he is to that responsibility.

Unfortunately, each theme seems to be sort of tackled at separate times rather than coming together in a properly cohesive manner. It’s also possible that the open-world nature of the game interferes with the narrative’s pacing, shifting my focus away from what the game is trying to tell me so that I can collect baubles and conquer challenges. When your attention is so easily pulled free from the story’s stakes, it’s hard to feel the intended emotional resonance.

I tend to spend enough time criticizing Western television, so let's have some griping and concern over two of the current popular shounen anime.

I’ve been quite open about my exhaustion with Western television in this column and on this website. Police and medical procedurals are so commonplace because you can craft a brand new crime, injury, or illness of the week while tossing in a good mixture of interpersonal human drama. Often there will be a twist, such as House M.D. and its cantankerous, grumpy protagonist. However, these shows are not developed with a sense of where they’re going, but an easily repeated formula with a key ingredient to give it some zip.

When the creators of Aqua Teen Hunger Force were tasked with creating a pilot episode, they were told that there needed to be a general structure or template that would “give viewers a reason to tune in each week”. So the first episode creates this illusion that they’re a crime-fighting trio that goes to stop whatever chaos the mad scientist has wrought in the opening prologue of the episode. However, this is all part of “the joke” for the creators, because that was never the show’s intent. Each episode is effectively written off-the-cuff and without any sense of direction. If Seinfeld was a show about nothing, then Aqua Teen Hunger Force is a show without purpose. Its pilot episode and opening animation are a complete joke regarding the network’s expectations of a silly, late-night comedy cartoon.

If I were to sit down and simply want something simple and reliable to fill the time, I’d likely have no issue with these sorts of shows. However, even when I’m exhausted I prefer my television have something to offer. I suppose my desire of entertainment is for it to revitalize me. While shows that rely on a formula can work well enough as an occasional comfort food, I’d rather my time be spent with something that “accomplishes something”.

Which is why shows like My Hero Academia and Food Wars! are simultaneously so delightful and so frustrating.