2021 in Review: The Indies I Played

My relationship with indie games has been an odd one. For a while there I was not quite taken by them, finding their titles to be a bit janky or unpolished even compared to their inspirational forefathers on 16-bit hardware built with more primitive tools. Only on occasion would I be floored by the craftsmanship of a title like Hollow Knight or Iconoclasts, games whose polish and effort was as top notch as the best of the publisher-supported studios.

I find that I’ve been languishing behind the times, as there are plenty of indie games out there of superb quality and often more befitting my interests than what the larger publishers have on offer. Unfortunately, I also find myself struggling to pick out the diamonds in the rough, or to find the titles worthy of standing alongside my favorites.

As a result, 2021 has essentially been the first year where I fervently began to pursue the fruits of independent labors, learning what does or does not work for me, and what I ought to be careful of when making purchasing decisions. Most of all, it has also given me plenty of independent publishing labels or smaller developers to keep an eye on in the future.

Curiously enough, I decided to immediately follow a playthrough of 2018’s The Messenger with Cyber Shadow. Each title had clearly been influenced by the original Ninja Gaiden series for arcade and the NES, yet Cyber Shadow was the far more linear affair as The Messenger had also sought to explore different pixel art styles and, therefore, different ways of interacting with the world. Once the path between 8-bit and 16-bit dimensions had been opened, the player was free to return to older zones and use their abilities to further explore a more open-ended world.

Though I feel as if I had enjoyed the gameplay of Cyber Shadow more, it simply did not have the same staying power as The Messenger. This is most likely due to the narrative of Cyber Shadow having little style and presence, whereas The Messenger was more amusing and creative in its time-and-space bending story despite inducing more than a few groans from its attempts at humor. Otherwise, I can only assume that Cyber Shadow is more vivid in my memory due to the more straight-forward approach as a linear send-up of Ninja Gaiden; it relies more heavily on combat mechanics to establish a fast-paced flow throughout a level than ponderous exploration and platforming. If you know what you are doing – such as whoever is in control of the gameplay footage in the trailer – then you’ll be able to speed through the separate maps at an incredible pace.

For one such as myself, however, I more often found certain levels and bosses a great source of frustration. This was especially true with the final boss, whose separate phases demanded a degree of perfection I found immensely frustrating to try and get right. It is curious that I’d find Cyber Shadow so frustrating and forgettable despite sharing a few elements in common with my favorite title of the year, yet I think what it comes down to is responsiveness and polish. Or, perhaps, whether the end result feels rewarding, or that I have actually improved rather than simply memorizing what buttons to press and when.

Polish and responsiveness would ultimately be the greatest enemy to many indies I played throughout the year, preventing me from properly loving them, even when I enjoyed them. Blue Fire looked to be a fascinating, 3D action-platformer inspired by both Dark Souls and the Legend of Zelda franchise, yet was never quite up to the standards of either. It certainly has personality, what with a cute looking mascot character and cohorts not unlike those of Hollow Knight. It also managed to pull in obstacle courses not unlike those of the Prince of Persia series, featuring puzzles of wall-running and mid-air dash timing to navigate halls and platforming challenges.

Unfortunately some of these courses demanded far too much precision for the floaty leaps of the protagonist, or simply lacked the necessary guidance or metaphorical signposts to even indicate where such a course was leading or intended to go. The foes and bosses were also somewhat obtuse at times, making for more than a few troublesome encounters.

Though as I write this, I must confess I somewhat wish to go back and play the game again. I suppose that alone speaks positively of the experience I had: despite recalling some awkward fights with opponents where my dodge did not execute as desired, or sighing in frustration as I searched the environment seeking some clue as to where I might go next, I also remember having a bit of fun leaping from wall to wall or timing my strikes against a mighty boss once they’ve left themselves vulnerable. Perhaps my memory is too unkind towards the game and it deserves a second chance. So while Blue Fire was certainly not one of the best games I’ve played this year, it was certainly enjoyable enough to at least begin beckoning a return out of curiosity.

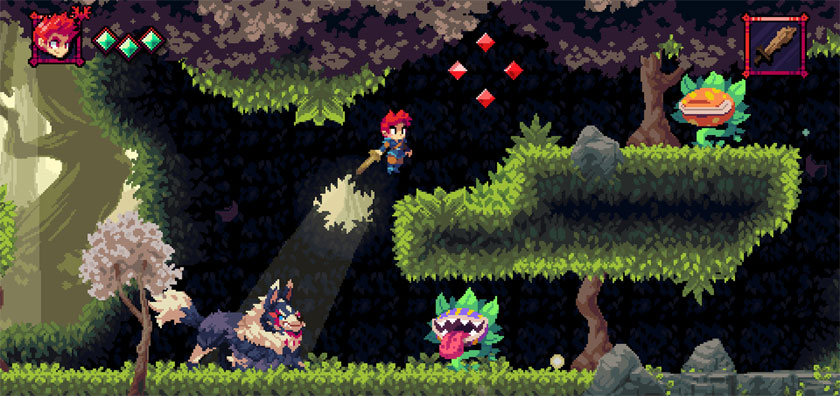

Flynn: Son of Crimson is not too dissimilar, its world and combat designed well enough to clearly indicate to a player what it is they ought to be doing. Perhaps this is one of those hard to iron out observations regarding certain games: some of the worst always leave the player baffled as to what the correct way to play is, while those that are mediocre, adequate, or simply fine make it clear what the player is supposed to do, but execution is somehow inhibited by the game itself. This could be due to controls that feel sluggish or unresponsive, a matter of animations being slow or not lining up with the player’s expectations, or the odd enemy that behaves unlike all others thus far.

With Flynn, it is a mixture of the occasional sluggish control and the odd behavior of an enemy. Most opponents in the game have clear attack patterns that allow the player to know when it is best to strike and when to dodge, or foes that flinch immediately upon being struck no matter what. Yet there are occasional opponents that neither flinch nor have as obvious a set of patterns, leaving very little room for the player to effectively swing and attack. This is particularly true of certain bosses whose attack patterns are so extended and lethal that it feels as if their fight is designed to take ten minutes each. Imagine how much of a pain it is to spend minutes whittling a boss down to one-third health only to die, forced to start over from the beginning! It happened on multiple occasions with Flynn, and in the end I could not decipher what I should have been doing since it did not feel I was playing “correctly”.

There is a balance to a game’s difficulty and challenge and whether the player themselves feels at fault for defeat or are left to feel as if the game is unfair. This is no doubt yet another subjective realm based on the player themselves or their own skill level, but I think the reason developers like From Software are known for being “tough but fair” is due to many players recognizing what they themselves ought to have done in any given situation instead. I don’t fully agree with those players, but I understand the sentiment. Shamus Young refers to it as whether a game feels “perfectable” or not. I think, perhaps, the answer lies somewhere between these options. Does Flynn: Son of Crimson feel “perfectable” to me? To an extent, yes, but one of the factors that prevents me from wanting to try and perfect my time with it is the simple feel of the game. To compare to an older title, Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy’s Kong Quest feels perfectly responsive when I wish to run, leap, or roll. It feels like a perfectable platformer because, even if I screw up, I need only improve my own reaction time or make small adjustments to my playstyle.

Flynn does not feel as smoothly responsive, and so when I get struck by an enemy because the character didn’t dodge when I pressed the button, it feels less like an issue with my response time and more like an issue with the game. In truth, it’s somewhere in between. I expect a dodge-cancel or am unable to read the enemy’s animation in time, but the game is expecting either a perfect knowledge of attack animation frames or knowledge of when to consistently strike and dodge to avoid damage. I want a game that responds with me, and Flynn is not such a game.

This is also somewhat my issue with Kena: Bridge of Spirits, a game which seems more preoccupied by its own animation prowess than the ability to make those animations intuitive for players. Admittedly, I am no animator such as Dan of New Frame Plus or Also Dan of Video Game Animation Study, yet it is their work that had first helped me consider what might be “off” about Kena.

To put it as succinctly as possible, Kena: Bridge of Spirits feels as if it is more difficult than it ought to be given its design. The speed at which Kena and her opponents swing their weapons and strike is not too dissimilar to other action games, and yet dodge or parry windows feel inconsistent in comparison to similar titles. This is, in part, due to an emphasis on how such abilities might be animated in a film; notable due to the background of the game’s creators. Kena’s defensive bubble will not appear until after she’s crossed her arms in a bit of a flourish, causing her parry or block to appear in more time than a hurried press and hold of the button might demand. As the Dans note, players of fast-paced action games expect for their characters to respond swiftly under certain circumstances, and defensive moves with precise timing are just such a moment. However, there also seems to be the lack of invincibility frames to Kena’s dodge, meaning the player must be very precise in regards to leaping out of the way of an incoming attack. However, the game does not possess an effective dodge-cancel in order to make up for this demanded precision.

It is small little details like this which clash with the game’s otherwise great polish. Exploration and puzzle solving all feel top notch, and once you’ve adjusted to the game’s subtle imperfections you can manage to dominate your opponents quite handily. This is especially true once Kena is granted her final combat ability, one in which the game would have done well to have awarded far earlier in its play time (though might have also trivialized some of the fights given how powerful it is). All in all, however, I was left with a game that I had enjoyed, but was not feeling the urge to immediately jump back into. If I’m feeling curious about replaying Blue Fire, however, perhaps that will change with Kena as well.

Regardless of my evaluation, Kena: Bridge of Spirits is one of the more high profile indie games due to being the team’s freshman effort and having the look and polish of an experienced game development studio. The only title perhaps more impressive looking that I played – and only so far as realism goes rather than aesthetic design – would be The Medium, Bloober Team’s latest “horror” entry with some AAA looking production value. It was one of the first games I had played in the year, an early title with which to use my Game Pass subscription on while testing out my PC’s new hardware specs, but you may also recall that I wasn’t wholly charmed by it.

The unfortunate perception of The Medium is due to the game’s obvious allusions and aspirations to be comparable to the Silent Hill franchise. The protagonist crosses between this world and what may be a plane of the afterlife, and the horror is more psychological than it is material. However, despite the efforts to be visually striking, nothing comes off as terrifying as the inspirational material. In fact, I’m not sure I ever once felt frightened or even nervous in my whole time playing.

If anything, The Medium feels like a concept too big for its studio’s capabilities. There are the beginnings of several ideas within, yet none are developed into their full potential. The protagonist can use certain abilities in the alternate reality, but they are never expanded upon or find alternate uses when exploring that realm. Everything is straight-forward, and it all concludes in a nonsense ending that feels more art school than it does auteur; an imitation of unconventional finales that provokes no thought and is intended to do little more than shock.

I did not dislike The Medium, but it is hard to be positive about it since the entire experience feels like unfulfilled potential.

Fortunately, there is Death’s Door, a game that I have also written about already. However, as I continued to play through different games throughout the year, my mind kept returning to Death’s Door as an example of a title that knew how to execute on its ambitions. Perhaps the overall reception in the industry feels more lukewarm than other games due to a lack of innovation in narrative or mechanics, but unlike so many other titles, Death’s Door never disappointed me. It was as responsive as I desired it, the writing was amusing, and it failed to overstay its welcome.

Most importantly, however, was that perfect design of enemy encounters. Not just in regards to arenas and unique gimmicks or quirks, but the assortment of what types of opponents and how many of each type. Playing games such as Kena: Bridge of Spirits throughout the year really drove home just how important it is to test and polish encounters to challenge the player without overwhelming them. Though I still found myself having a rough time at parts, I never felt as if Death’s Door was tasking me with completing an unreasonable fight. Even when I had gone through a second time to restrict myself to the umbrella, the weakest melee weapon in the game, I always found the skirmishes challenging but possible to overcome. “Tough, but fair” as they say.

I feel as if Death’s Door truly goes unrewarded in that regard. Yes, it also has a series of enjoyable puzzles to progress through, and the post-credits endgame is delightfully open and explores more of the world literally and figuratively. Ultimately, however, it is the best indie game I played without a doubt.

I would, however, like to conclude by offering a note towards Mighty Goose, an old-fashioned and silly arcade game that would likely be a lot of fun to revisit with a friend. It can be beaten in a single play session, though there are a few abilities and secrets to go back and find should you choose. Not unlike the arcade games of old, this is an excellent title to kill an afternoon with, its combat excellently polished and mech-piloting goose gimmick being silly enough without also being shoved in your face. It was a delight to play, and the only flaw I can think of is the manner in which so much ends up happening on the screen that you can easily lose track of enemy projectiles.

There are plenty of other indie titles that released in 2021 that I have not been able to get to, or have only just begun to tackle on stream. Dreamscaper, for example, is a cozy little rogue-lite where you explore your city neighborhood during the daytime before diving into haunted memories in your dreams. It lacks the same polish that makes a title like Hades so worthwhile and playable, but if you’re a fan of the genre then it’s certainly worth giving a try. As of this writing I’ve been streaming Smelter, an interesting fusion of Mega Man Zero style inspiration with the overworld strategy and tactics of ActRaiser. It suffers a bit from the responsiveness issues that Flynn: Son of Crimson has, but has otherwise been rather interesting.

I’ll be on the lookout for plenty more in 2022, but I’ll also be careful to look at user reviews rather than simply relying on flashy trailers. Despite approaching these games knowing they are unlikely to accomplish what the higher budgeted compatriots can manage, I’m more likely to be impressed and addicted to titles such as Hollow Knight or Iconoclasts, which occasionally put the more expensive releases to shame. Hopefully there will be just such a title in 2022 to wow the pants off of me.