2021 in Review: The Year of the ‘Vania

It is no secret that my favorite Nintendo franchise is Metroid. I’ve even played some of the “worst” games in the property multiple times, finding something of value in each title. Despite the indie scene exploding with imitations in the “Metroidvania” genre, however, there are few games that properly sucked me in as much as their mother inspiration.

I think there are multiple reasons for this, one of which being a shift in creative direction on part of the developers themselves. Hollow Knight, for example, is a far more ponderous world. While the Metroid series is certainly an inspiration, it is only one of many, including several more platform-intensive games of old and the recent rise of the Souls-like. My first impression of Hollow Knight was initially positive, but eventually grew more exhausted as I had felt directionless and as if new abilities and power-ups were coming all too slowly. It was only after I had played through Bloodborne that I understood how much From Software’s atmosphere and world design had combined with the inspirations of Metroid to form Hollow Knight’s expansive world, one in which player choice of exploration was emphasized. Once I had that fresh new perspective, I was able to appreciate Team Cherry’s game as its own thing rather than comparing it to the Metroid franchise I knew and loved.

There has always been one other element of the equation missing, however, and that is the “-vania” portion of the genre title; I’ve never truly played through a Castlevania game, despite the franchise sharing a variety of traits in common with my beloved Metroid series. In 2021, I had begun to try and correct this.

Technically I had already begun to explore the Castlevania corner of the genre with Bloodstained: Ritual of the Night, a game which I had replayed earlier in 2021 and developed greater appreciation for. Unlike my initial experiences with Symphony of the Night and Hollow Knight, Bloodstained felt far less “meandering” and directionless. It was more limited in regards to where protagonist Miriam could or could not go, taking its time to expand the number of possible routes to explore rather than present several options at once. Little did I know that it was somewhat of a compromise between the open-ended design of prior Castlevania titles and the “more linear” paths of the Metroid franchise.

The visual aesthetic and manner in which Deedlit walks is very much in the style of Symphony of the Night.

In truth, however, it was the efforts of Team Ladybug that had me curious about returning to the influential gothic horror franchise due to their obvious inspirations. The manner in which protagonists in Touhou Luna Nights and Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth moved were clearly modeled after Alucard in Symphony of the Night, as were the map designs and general aesthetic of their environments. It is true that each game is based on a pre-existing property, but an emphasis on dark interiors and the purchasing of weapons and magic spells steps away from the permanent power-ups and sci-fi tech of Metroid.

Having enjoyed both games immensely, I finally chose to sit down and play Castlevania: Circle of the Moon, remastered as part of the Castlevania Advance Collection. Admittedly, I’ve wanted to try this game out for a long time if only because I passed over it during the launch of the GameBoy Advance. Having gone back and completed it, I do feel that I might have greatly enjoyed it during my high school days. I was unaware of the save states for the majority of my playtime, meaning I dealt with the difficulty as much as I would have if I’d played it in its original state, so I found myself getting frustrated at a number of deaths and forced restarts at different points. I am not ashamed to confess I had sought guides for some of the bosses during this playthrough as well.

It was certainly more difficult than I had anticipated, though in part due to the “stiffness” of the game. It is unfair to compare a twenty year-old game to more recent releases with the benefit of modern polish, but Hollow Knight, Touhou Luna Nights, and Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth all certainly felt far better to play than Circle of the Moon had. However, even if we wish to be fair and compare to games of similar age, Metroid Fusion featured a far more agile and acrobatic Samus Aran than Konami had offered with Nathan Graves.

This is one of those areas where I have learned to approach the Castlevania franchise on its own terms. It is a more “old-fashioned” combat design doing its best to work around limitations rather than push through them. Even as I play Symphony of the Night – which, admittedly, feels more smooth in regards to how Alucard controls – it feels as if the combat relies on some gimmicks or tricks in order to avoid damage rather than something more acrobatic and polished.

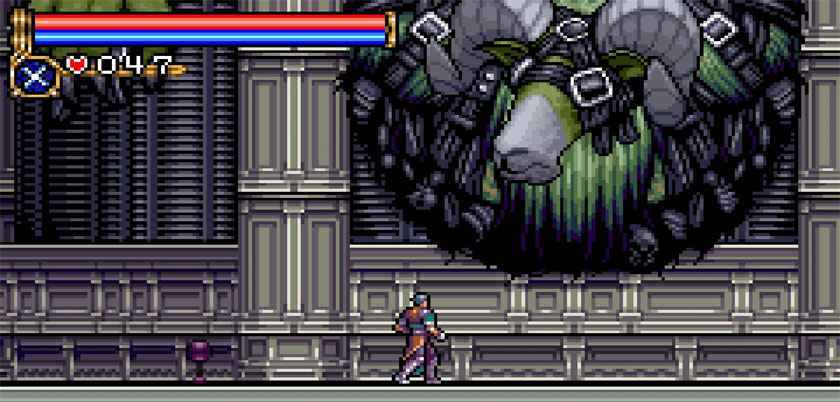

Just another boss I feel like I mashed some buttons through in Circle of the Moon.

It’s difficult to illustrate my precise meaning, but I suppose it’s more that Castlevania is based less on reflexes and more on timing, positioning, or even exploitation. Alucard is too slow and stiff to immediately respond to most attacks with proper evasion, so even if you manage to activate his back-step, he could quite easily remain in range of the enemy attack. Samus, however, is already light on her feet in Metroid Fusion and can leap away from an attack with ease. So both Circle of the Moon and Symphony of the Night become a sort of rehearsed series of steps where you learn an opponent’s attack patterns, step in range just long enough to take a swing or two, then leap away or back-step enough to be out of range of their next attack. That, or you find a spot to consistently crouch or a tool to frequently use to take the enemy down. It’s more methodical than it is reflexive and in-the-moment.

Not that the older Metroid games lack similar approaches to combat design or feel. However, since hitting the sixteen-bit era, Samus has become more and more about speed and agility (in her 2D games) while Castlevania’s protagonists seem to move at the same slower pace as they always have. That in turn impacts how combat plays out.

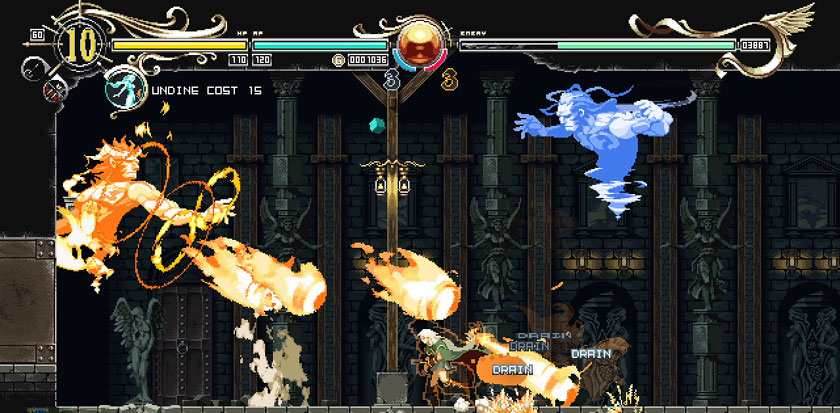

It is no doubt obvious that I prefer one over the other, which is why I thus far find Touhou Luna Nights and Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth far more enjoyable experiences despite being modeled very heavily after Castlevania. The two also take influence from outside the typical Metroidvania genre by implementing “Bullet Hell” style mechanics. With Touhou Luna Nights, it relies on the player to make use of their time manipulation abilities in order to freeze or rewind enemy attacks which take the form of “bullets” that often flood the screen. In Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth, the titular protagonist gains the assistance of Wisp and Salamander spirits in order to resist damage from similarly colored elemental “bullets” while alternately dealing additional damage to opponents of a contrary affinity. Each game has a faster paced combat focus while adding additional mechanics that increase the importance and emphasis of evasion and, in the case of Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth, providing healing to a maxed out elemental charge; yet another tactical consideration to be aware of, as once you’ve been struck physically you lose your charge and therefore your healing. If the alternative element is fully charged, you can swap out to that, but if you do so while stunned or otherwise in the middle of a barrage of attacks, you may risk getting struck again and losing both elemental charges, thus leaving you without healing.

Even if I am biased to prefer these games for their smoother, more agile combat, it is still unfair to compare them as they have the twenty year benefit of improved technology and broader inspiration to draw from.

An early boss fight in Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth that requires careful management of elemental affinity both defensively and offensively.

What I will concede, however, is that the Castlevania games are perhaps stronger in providing the player a sense of “freedom” that the Metroid games do not. Studying the analyses and opinions of other Metroidvania fans over the past few years has revealed to me that many players value a greater degree of freedom of choice in how they approach a map and its objectives. Nintendo has never, in either their best or worst games of the bunch, allowed players to stray too far off the critical path. Any accessible branches are strictly lateral and only provide boons rather than necessary objectives to complete.

I attributed Hollow Knight’s more open map design to the Souls-like games, but that is only partially accurate. The Castlevania games themselves seem to have a tendency to “open up”, allowing the player several portions of the castle to explore and discover rather than having a very specific path forward. What I once thought was “meandering” was actually a decision to give me freedom to tackle whatever I want. So if I happened to progress through a tough zone only to die to a boss afterwards, I could look at the map, see what other unexplored areas remained, and go see if there was another path available to take. Most of the time there was, and often just such a path would reward me with a new ability to push onwards and perhaps even ease up the challenge in the zone I had died in.

It is this realization that has contributed to my greater enjoyment of Symphony of the Night, enough so that I have no doubt I’ll complete it this time (and, yes, I aim for the “true” ending). Moreover, it may help me to better appreciate other entries in the genre far more.

After all, what I have come to realize is I was directly comparing each Metroidvania I played to the Metroid games, period. I cannot change the fact that I prefer Nintendo’s approach to the genre even as so many other players and critics yearn for the games to become more open. If you were to make Metroid more like, say, Hollow Knight, then you’d lose much of what it means to be Metroid specifically.

However, though Touhou Luna Nights and Deedlit in Wonder Labyrinth are more “linear” in the manner that the Metroid games are, they still don’t feel like a Metroid. That’s okay. Their map design is somewhere in-between that of the Castlevania games, and their combat is closer to the fast-paced, acrobatic style I prefer. This means, however, that I will approach Castlevania with a different perspective of exploration than the other games. In turn, I will no doubt also approach other Metroidvanias with a broader reference point to see in which elements they choose to take inspiration, as well as where they choose to try and differentiate themselves from the foundational franchises of the genre.

No doubt there will be plenty more ‘vania to discuss in 2022 as a result.