Caligula Effect: Overdose

My brain feels “disappointment” is an accurate descriptor of Caligula Effect: Overdose. My heart feels the term is too harsh, and would prefer to impress upon you the nature of the game as ambitious but flawed. On paper, it is one of the best games I’ve played in years. In execution, its greatest elements are outweighed by its most simple and tedious of design choices.

The last time I felt this way was with Akiba’s Beat, a game whose story struck me at a vulnerable point in my life and resonated in ways no other game in 2017 could. However, it’s dungeon-design was such that I developed a strong loathing towards the game and its repetitive, back-and-forth side-quests that endlessly recycled the same tiresome corridors without end. It was a pair of extreme reactions, with a deep love for the game despite a savage hatred for its flaws.

Only I don’t feel so extreme towards Caligula Effect: Overdose. I enjoyed its writing greatly, and it should have resonated with me deeply. For whatever reason, however, it did not. Perhaps because I’ve grown more accepting of my life and no longer dream the sort of escapist dreams I had in my youth. The game implemented a lot of the same flaws of dungeon design as Akiba’s Beat, but under most circumstances the combat was easier to avoid and thus dungeons easier to simply skip through. So while I did not enjoy the gameplay as much as any player would like from a game they purchased, it also did not frustrate me to the point of absolute loathing.

In the end, Caligula Effect exists in some Schrödinger state of recommendation. There’s enough neat ideas and excellent writing to be enjoyable, but the actual playing feels so lukewarm that I am woefully uncertain I’ll even remember having played it by year’s end.

Such feelings could easily have been avoided if the game were designed with more carefully constructed combat encounters in mind. Playing on the Hard difficulty, I often found boss battles and encounters with multiple opponents the most challenging, demanding I plan my attacks out far more carefully.

Not that your plans will always succeed. The game has a most curious structure where your commands occur in two phases. The first is the planning phase, where a projection of what your character’s actions will cause should they succeed plays forth. Each character can perform up to three actions, though it sometimes benefits to only execute one or two. These commands and the amount of time they occupy begin to fill a sort of timeline at the screen’s top, one which I am certain is intended to resemble a user-friendly, electronic musical timesheet. You see up to “two measures” of combat in preview, and as you give each character commands you get to see their actions outlined upon this sheet. How long the wind-up takes, the actual moment of attack, and then the cool down.

This system is given depth by enemies having several types of attack. Certain melee blows will be able to be countered by specific attacks, as can ranged strikes by different types of attack. Some attacks can pierce through an enemy’s shields, avoiding the stun that normally accompanies a strike to these energy-based barriers. Yet enemies have plenty of blows that cannot be countered, and therefore the player must time their own emergency barriers to block their opponent and stun them. As the game progresses, there are some blows that cannot be repelled by the barrier.

This is where, perhaps, the most important element of combat comes in. Each enemy has a “Risk” meter that can fill up to six times. On that sixth fill, the enemy achieves a “Point Break”, where any action currently being done by the opponent is interrupted, all strikes deal critical damage, and they are stunned for a time. This Risk meter builds as the player attacks the opponent, and certain moves will allow the player to “launch” an enemy once their skill meter reaches a certain state.

So by combining basic counter moves to the different categories of attack with moves designed to counter opponents of a certain risk level, a skilled player can plan out a series of attacks that cancel their opponents’ offensive moves and even keep them juggled in the air, or subdued on the ground in a prone state. It is certainly one of the most inventive combat systems I’ve played in a while, and on Hard mode there were certainly plenty of fights that had me biting my nails in concern I wouldn’t succeed. The success of achieving a Point Break on a boss in particular was always satisfying.

There are certainly other elements to combat, such as support abilities that buff and debuff or each character’s special “limit-break” style moves. Ultimately, however, the combat is about making sure your opponent can execute as few moves as possible, and while up against particularly troublesome foes, that may require playing extremely defensively while still somehow managing to build that Risk meter up.

This combat system could have made Caligula Effect: Overdose one of the best games of the year. However, there’s more to a combat system than its actual design. It is the speed and circumstances at which it can become tedious and repetitive. For most dungeons, it’s easy enough to avoid combat should you choose. If you wish to engage, it’s even easier to find a moment with which to strike the enemy from behind, allowing you to begin combat with the enemy already at Risk level 4, and therefore ensuring any type of early strike will launch them into the air and set them up for a Point Break. Moreover, you can make sure you fight only one enemy at a time.

Even on Hard difficulty, one enemy at a time is absent of any real challenge. It is true that other enemies can join in on the battle at any moment, but under most circumstances these fights can be completed well before the new challenger is ready to cross into the battlefield. While the player has Auto-Battle options, you ultimately input the same commands over-and-over, wandering featureless labyrinths that are intentionally designed to be time-killing corridors, padding out the game’s length to be something “more appropriate”.

A far better choice would have been to take inspiration from tactical role-playing games, where each encounter is specifically crafted and designed. Offer options for random encounters should the player choose to grind, but otherwise leave the majority of story and side-quest progression as unique encounters that intentionally select opponents of specific abilities to complement one another and challenge the player.

Instead, the vast majority of the game is spent either dodging combat or easily crushing opponents one at a time, each encounter padding the game length out by another minute or two. This naturally coincides with minor design choices that only match the tedium, such as the inventory screen being a massive list of “items” akin to the original Mass Effect’s. When the original Final Fantasy on the NES has it figured out better than your modern game, there are major problems.

If there is anything that saves the game it is the writing and ambition. As I stated earlier, the timeline of combat is, I believe, intended to be reminiscent of some electronic collection of tabs or some other alternative to a traditional musical score. This would tie into the player’s companion being one of the two Virtual Idols that helped construct the virtual world the characters are trapped in, their combat prowess a manifestation of their pent up inner rage just as music tends to be a manifestation of one’s feelings in a melodic form.

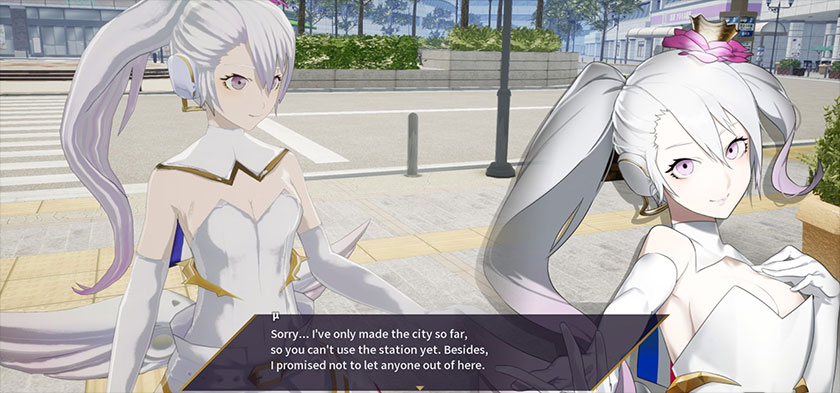

Which is just the beginning of what makes this game’s premise fascinating. Despite being another story where the characters are stuck in a virtual world, this isn’t a world designed to be a video game. It is a world designed as an escape from the pains of reality, where everyone can forget about the discontent of their lives and return to the simplicity of high school life, all of the things they believe they want available to them.

Anyone that’s been paying attention to anime and the state of Otaku for the past decade is no doubt going to understand the concept driving this game’s setting. The obsession with escapism to the point that it completely removes one from reality, living in a perceived utopia with even the worst of traits being enabled. Curiously enough, one of the flaws of this setting is a simple truth: you cannot make everyone happy. The fantasies and desires of some are in direct opposition to the fantasies and desires of others. There will inevitably be conflict. There will inevitably be negativity.

Which is where our antagonist comes in. What perhaps drew me to this game in the first place, aside from its stylish visual representation and character design, was this interview with Game Director Yamanaka Takuya.

“In Japanese spirituality and folklore, there’s a common theme in the concept of humans fighting against gods and defeating them,” Yamanaka said.

“It was an appealing narrative theme because it’s something that was very taboo, of course, and as such a lot of people found the idea fascinating. But lately, people in the current era, they don’t believe in gods anymore, and they’re moving more towards worshipping idols or famous TV stars. People are more inclined to believe in them instead of a god.

“So we can see that Hatsune Miku is a kind of saviour and being to believe in for the young people in the current era. If you take someone like her and actually defeat her… well, that would be the equivalent of god killing of this era. That’s how μ came about.”

It was this notion that really got me hyped up and paying attention to this game. Killing God is perhaps one of the most common tropes of Japanese Role-Playing Games, yet here in Caligula Effect Yamanaka was encouraging the player to kill that which they worshipped today. However, he didn’t make the Idol malicious. Instead, he made the Idol as kind as possible. She is the exemplary Idol, all actions done in love and support of her followers and fans. Where Tokyo Mirage Sessions #FE delivered just the fantasy of the perfectly devoted Idol that its fans would yearn for without proper examination, Caligula Effect shows just how destructive it is for a being – even a virtual one – to constantly work towards the happiness of others without regard for themselves.

If Caligula Effect: Overdose appeals to me in any great fashion, it is that there are no characters portrayed as lacking redemptive qualities… well, aside from one, and he happens to be on the side of the protagonists. That’s part of the twist. The most despicable, selfish, uncaring individual is not on the side of the antagonists. He’s on the side of the players, desperate to break free of this artificial reality.

Which is the real dividing line between protagonists and antagonists. It’s not about malicious intentions. It is about the willingness to face your own weaknesses and flaws and work towards bettering your life, or instead choosing to enable the unhealthy behaviors and fantasies that do not improve or change the situation. So, as someone that is overweight, it would be the choice between me going to the gym, disgusted at my appearance in the mirror, exercising hard and removing bad items from my diet… or simply going to the store and replacing it all with fat-free variants of what I love while continuing to indulge in massive portions of food. The only difference is that latter option comes with no consequences in this fantasy world that the Virtual Idol built.

The player doesn’t have to get to know anyone, and can in fact choose sides if they so wish. There are three endings that I’m aware of based on player choice, and I’d gladly go in and explore all of them. There’s a lot of fascinating themes in this game regarding escapism and the struggle of life that feel unique to Caligula Effect.

Unfortunately, even a New Game + requires the player to suffer through those time-padding dungeons and their labyrinthine hallways filled with tedious encounters.

So I sit here, uncertain of whether this is a game worth recommending. I enjoyed the story, and I’d love to return to it one day. Yet I feel no need to really go back and “explore” its combat further, even on harder difficulties. It is a game I played, I’m glad I played it, but I don’t have faith I’ll remember it like I have games like Nier: Automata (which, to be fair, had a far better budget and developer) or Akiba’s Beat.

Nevertheless, if anything in this write-up intrigued you, then I say give the game a look at some point. At the very least you’re sure to find joy in parts of it.