Danganronpa: Trigger Happy Havoc

It is not at all possible for the concept of wa or harmony to completely disappear in Japan. The disappearance of wa would mean that the Japanese would cease to be Japanese.

Masayuki Tamaki

This quote is used in the introduction of You Gotta Have Wa, a book written by Robert Whiting about the culture clash between America and Japan through the sport of baseball. It has been a fascinating read, adding further context and understanding to basic concepts I only knew of on a surface level: fighting spirit, honne and tatemae, and that of wa itself.

I enjoy reading about this stuff because it further enriches my perception of a lot of Japanese entertainment. Character decisions that otherwise seem foolish or baffling in an American context can be better understood when you know how the concept of “face” differs in Japan. I’m admittedly no sociologist, but ever since I began learning of these things I’ve better caught on to themes and ideas I otherwise would never have grasped in Japanese entertainment.

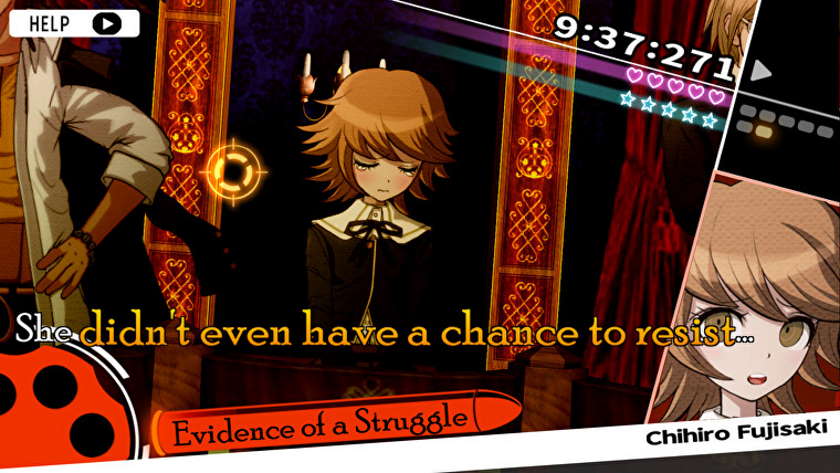

Which is why Danganronpa was such an enthralling game to play. On the surface it’s some twisted highschool murder game hosted by an unsettling robotic mascot bear. Its fur is divided between a white-and-cuddly half sporting an innocent smile while the vicious-and-black half bears sharp teeth and a fierce red eye. The contrasting halves represent the dueling concepts of hope and despair that serve as the story’s core.

To focus exclusively on these broad ideas would be to miss the game’s true depths. By time you reach the game’s final conclusion, it will feel truly absurd and off the rails. Just as similar visual novels 9 Hours, 9 Persons, 9 Doors and Virtue’s Last Reward seem to climb further and further over the top of belief’s suspension wire, Danganronpa escapes the realms of reality and bursts into some strange alternate universe that nearly distracted me from the big picture.

The absurdity that the game reaches is an exaggeration used to stress ideas about Japanese school life. Specifically, the black and white contradiction that seems to exist regarding Japan’s emphasis on wa and the cut-throat nature of academic standing.

Over the past several years, headlines featuring Japanese students regularly cleaning their schools or assisting in lunch service have spread across social media as a model for other nations to follow. By making such duties mandatory in school, students are taught to be respectful of their surroundings, of others, and to take personal responsibility in their environment. Fans of anime have no doubt seen examples of cleaning duty in their favorite shows, such as Shinji Ikari observing the motherly nature in which peer Rei Ayanami wrings out a washcloth in Neon Genesis Evangelion.

It’s only natural for a culture where wa is so highly valued that it would teach the student body that we’re all a part of a greater whole. The lesson learned is that we must all harmonize and work with one another in order to function as a society.

Yeah, I’m definitely going to have to make a video of this game and its potential readings some day…

Unfortunately these articles gloss over the problem of suicide rates among Japanese children and teenagers, an issue that can occasionally be attributed largely to bullying. However, the phenomenon known as Examination Hell is a culmination of pressures both social and academic to perform well. Failure to succeed on an exam could similarly be viewed as failing one’s whole family. While College education is widely available in Japan, there is only a small percentage of high-ranking and private institutions whose acceptance is viewed as guaranteed life-long success. Institutions with very limited openings available each examination season.

If the white half of Monokuma is wa, then the darker half represents the despair caused by the cut-throat competition that occurs during examination season. Thus the stage of Danganronpa is set. The characters are encouraged to live together in harmony, but should any one student wish to “graduate” they must kill a fellow student in secret. If they manage to fool their peers during the Class Trial and misdirect suspicions to someone else, the murderer goes free and the remaining students are slaughtered. The player’s goal as protagonist Makoto Naegi is to suss out the truth and make sure the murderer is the only one found guilty. Once revealed, the murderer is “punished”, summarily executed before those that might once have been called friends.

In other words, the students are expected to pretend to live in harmony with one another, but the system itself encourages them to act in self-interest. As the “game” continues, Monokuma pressures our cast of characters with a motive. The lives of friends and family are threatened first. Then, everyone’s deepest secret is threatened to be revealed to the whole world. Finally, money itself is promised to one that would kill.

Each chapter is almost like an examination of the different facets of Japanese culture and the manner in which they combine to create this pressure cooker environment. From obligations felt towards family and friends to the promise of monetary gain, Monokuma does his best to coax each student into “graduating” from school. Just as with the novel and film Battle Royale, our teenage characters learn that they may not have known their closest friends as well as they thought. How tatemae – the outward mask worn out in society – obfuscates their honne – their true feelings often reserved for family and close friends. From simple deception of those once believed to be allies to the desperation to keep a dark, humiliating, shameful secret buried, each student is an exaggerated reflection of the kinds of pressures regular students in Japan feel. There is a heavy weight of expectation upon them, and Monokuma seeks to crush them with despair.

I’ll probably cover the actual game mechanics after playing the sequel title.

Which is where we reach the over-the-top absurdity of the game’s conclusion. Danganronpa isn’t just a metaphorical examination of the trials of Japanese academia, but asks what is it all for? From the nineties to the aughts, Japan has been the victim of roughly twenty years of economic troubles. The once regularly expected life-long employment is now a rare commodity. The class gap is spreading ever wider, and marriage and birth rates are low. Even if you graduate, what promise do you truly have of a future?

It is through this lens that Danganronpa’s hopeful conclusion has meaning. As the credits rolled I felt as if the team at Spike Chunsoft were trying to leave me with a very optimistic message. “We may not all make it. Some of us may succumb and break under the pressure. There’s no guarantee that the world won’t do its best to beat us into a pulp. But those of us that make it can still do our best to try.”

A message that any graduating student or adult can no doubt appreciate, but one that must have resonated deeply in an economically uncertain Japan.

I loved this game. I was hooked to it, and while my first response to its concluding chapter was a negative one – the overly verbose exposition drags the final trial out for too long – I came away with an understanding of why the writers took such an odd, over-the-top turn.

I can only hope that there were students in Japan that played this game, seeking an escape from the despair that weighed them down each day at school, only to find their hearts lifted by the optimistic message provided at the game’s conclusion.