Elden Ring Piece-by-Piece: The Open World

This article is the second in a series exploring the game Elden Ring and its design. You can read the prior entry here.

Ever since The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild released I’ve found myself debating what makes a “good” open-world with my friend and titular podcast cohort Steve. After five years and an additional one-hundred and fifty hours in Elden Ring, I think I’ve come to recognize just how much of that debate is over the unimportant specifics. While icons on a map are a part of the problem to someone such as myself, it does not get to the heart of what I enjoy about an open-world. Towards the end of our ninth conversational grab bag, I asked a simple question:

What is the point of a giant, open world if you don’t even engage with it?

Of course, this question itself could easily lead to more semantics and unimportant bickering over minor details. From my perspective, however, if I’m following the GPS on the mini-map or looking for icons rather than topography, then I’m not actually engaging with the world. It simply exists to look good on screenshots and pad time between linear missions or mini-game style activities.

Again, this is from my perspective, and I’m not even sure what forms the foundation of that perspective. All I know is there are some activities that exhaust me when exploring an open-world, and others that do not. When I played Breath of the Wild, I found it refreshing to explore a mountain range only to discover a hidden shrine or, even better, a dragon roosting upon its peak. There was no icon on the map saying to go there for that thing specifically. It was… well, it was a discovery, and it was driven purely by my own curiosity. When there’s an objective marker present, I tend to look at the mini-map more than the environment around me. When no such marker is present, my eyes are instead scanning every bit of the world, and this activity allows me to appreciate the world even more.

It is this same sense of discovery that embodies Elden Ring, but unlike Breath of the Wild, the Lands Between are far less accommodating than even the harshest corners of Hyrule.

The player is free to go wherever they want once they step out into Limgrave for the first time. Yes, you are free to attack the Tree Sentinel, inadvisable as it may be. You can completely ignore the Lost Grace or White Masked Varre before you, and can even choose to head East towards a swamp or forest instead of West to the sanctuary of a ruined Church. Most of these decisions are likely to result in the player’s death, but they are possible nonetheless. Players can even avoid making a pact with Melina altogether, forsaking not only the ability to level up, but the faithful steed Torrent who expedites travel across the vast continent.

This sort of freedom is one of the secret ingredients to the game’s success in the open-world genre, though it can simultaneously be a detriment to impatient new players. There are complaints across social media and Reddit of players that kept trying to fight the Tree Sentinel, failing, and declaring the game is unfair and utter garbage in so many colorful words. Others will exclaim how genius the Tree Sentinel placement is, “teaching” the player that they are free to flee or avoid confrontations, be it in their entirety or until they return better equipped and far more powerful. Similarly, should the player follow the guidance of grace directly to the bridge before Stormveil Castle, they’ll be “taught” by Margitt that they don’t have to keep banging their head against a challenging boss: they can turn around and explore the world instead.

Only these aren’t really lessons to the player in the typical sense. A lot of YouTube essayists trying to sound academic and insightful have made such claims about these two particular bosses, but Elden Ring isn’t actively instructing the player of anything. The player is free to choose; it is up to them if they choose to “git gud” and bang their head against the wall of a difficult foe or turn around and seek what armor, spells, or lesser challenges the Lands Between have to offer. If these bosses were to represent a test, it would not be an evaluation of knowledge so much as an observation on patience, stubbornness, personality, and thought processes.

It is far more accurate to say that the Tree Sentinel conveys a simple message of awe-inspiring danger to the world. It is not a monstrous creature that stalks the wilderness of Limgrave, but a gold-clad knight riding upon a decorated steed, conveying a sense of pride, renown, and honor. You, however, are Tarnished, and evidently that means you are an intruder to the Lands Between. So, players may choose to fight the Tree Sentinel, or they may choose to avoid it. The latter is the most likely choice, and by doing so players will begin their first act in engaging with the world of Elden Ring. How does one avoid the Tree Sentinel? Which bushes does one sneak through to evade detection? How about running a bit far to the North or South-West to just circle around the Sentinel’s territory? Maybe just sprint right through and hope the majestic rider doesn’t run you down?

This hilltop statue stands out no matter which direction you approach it from, ensuring the player’s eye will be drawn to it.

As the player evades the Tree Sentinel, it is possible their eye will be drawn to other potential landmarks. There’s a pathway down there, towards ruins and a beach! Perhaps there’s a secret down the — oh, nevermind, there’s a mighty large troll creature with a giant sword on its back climbing up that hill. Perhaps we’ll come back another time. Oh, what’s that statue up over yonder? Ah, upon further examination it creates a pale blue light illuminating a path towards the distance. Oh, but there’s a fire within that ruined Church, which… ah, yes! This is the next point of grace, where the previous had been directing me! Excellent, I’m now officially past the Tree Sentinel and have guidance to my next destination, while simultaneously having uncovered other potential paths I could explore now or save for later.

This opening experience is effectively a bite-sized introduction to the game proper. The world is littered with foes, secrets, and sanctuaries alike, and the player is able to decide how to engage with these things however they want. Or, at least, almost.

In The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, you can collect korok seeds by completing minor puzzles scattered throughout the world. These seeds are currency with which one can expand their inventory size. However, in order to trade these seeds for carrying capacity, you must first find the large woodland creature Hestu. If you follow a specific route through the beginning of the game, then you’ll inevitably stumble upon this character. I, however, did not follow this route, and therefore found myself with a very limited inventory for twenty-some hours of gameplay. In fact, I might have taken down the first Divine Beast without having met with Hestu.

That you can only meet the character in one specific place in a game that boasts freedom was, to me, always one of Breath of the Wild’s flaws. Unfortunately, Elden Ring is somewhat similar, though not nearly so restrictive. Melina will not appear before you until you reach a specific grace or number of graces activated. In addition, the player is unable to access the Roundtable Hold until they’ve at least encountered Margitt, activated a specific grace or graces in Caelid, or headed for the Weeping Peninsula. This puts a limit to how much a player can upgrade their weapon while exploring Limgrave. Additionally, if players wish to enhance their Spirit Summons, they’ll not only need to speak with Roderika just beyond the Gatefront Ruins, but will have to infiltrate Stormveil Castle quite deeply to uncover the item necessary to send her to Roundtable Hold herself.

Just leap forward and you’ll be on the path to Liurnia, bypassing Stormveil Castle and its overlord Godrick the Grafted.

Such specific step-following goes against so much of what makes the game work otherwise, especially on repeat playthroughs. As stated, this game has a lot of freedom, and some of that includes being able to sprint past the exterior walls of Stormveil Castle to find a narrow passage skipping right towards Liurnia to the north, or to march right into rot-infested Caelid to the east. You can even use a teleportation trap in the Weeping Peninsula to the south to skip right into the city of Leyndell, though I do not recall just how much freedom is afforded the player (I was too cowardly to stick around and teleported “back home” as soon as I could). If the player has a weapon, armor piece, spell, talisman, or any other item they know the location of, they are free to head directly there as soon as they wish. There is literally nothing stopping them from accessing the majority of Elden Ring’s content early.

Yet in order to upgrade weapons or spirit summons, they must follow more rigid steps that interfere with that same sense of freedom. It’s not as bad as Hestu in Breath of the Wild, admittedly, as the game does manage to take the player’s multiple possible paths forward into account. Nevertheless, too much is still predicated on following specific steps, and this is especially true in regards to Roderika. To some, this will be a major problem. To others, I no doubt sound like I’m nitpicking, digging for something to complain about.

Regardless, the game is not entirely free anyway. Unlike Breath of the Wild, Elden Ring does not permit the player to charge right into the den of the final boss. There are a few necessary steps that must be taken, typically in the form of felling a requisite number of key bosses before accessing a portion of Leyndell Capital. Whether this is a flaw or not is up for debate, as the primary method of engaging with the Lands Between is by looking for fights. It is the main draw of the Soulsborne legacy of games, after all, and that continues here. In addition, given just how free the player is to explore the rest of the game world, it truly does beg the question of whether it really matters that there are a few progression steps necessary for beating the game.

Even then, I find the freedom itself to just be one component of the game’s open-world being such a success. Another is certainly not new to Elden Ring, nor was it new (or as rigidly executed) in Breath of the Wild: constructing the world so that it is divided between biomes or zones. Many prior open-world games, such as inFamous and even the recent Ghost of Tsushima, would lock a player into a single zone with a set number of activities available to complete, only to allow them access to the next after completing enough story missions.

Elden Ring is constructed similarly, only there are no icons or percentage markers informing the player of just how “complete” a zone is. Nevertheless, it still has a similar effect on the player, allowing them to compartmentalize each chunk of land into a sort of progression-based zone. Limgrave and Weeping Peninsula are the early-game zone, followed by Liurnia as the next, and from there to explore Caelid, Altus Plateau, or a potential third zone down a curiously located elevator. Unlike inFamous or Ghost of Tsushima, a player isn’t exploring for the sake of completionism or unlocked trophies, but for the sake of discovering new treasures or foes so that they might be strong enough to challenge the next region.

At least, this is the logical process for a new player. Experienced players, however, are once more free to cut through to whichever zone they desire, taking on advanced challenges with the foreknowledge of a prior playthrough, or simply taking a shortcut to the most ideal gear for their desired build while leaving all other trinkets behind. This knowledge, however, is gained by… well, if we’re being honest, it’s most likely gained through Wiki guides and YouTube videos, but even without such things a player may loosely remember quests, upgrades, or locations from a prior playthrough. I myself had done just such a thing to collect more smith-stones, skipping from Limgrave to Liurnia and Caelid so that I might upgrade my blade to better tackle the foes in Stormveil Castle.

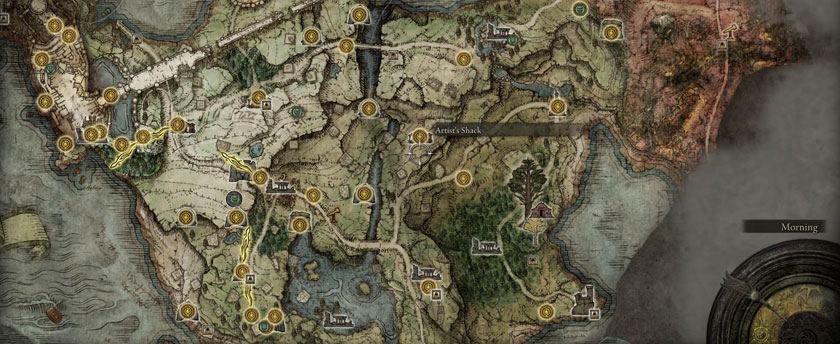

To that end, the world is as large or small as you need it to be, and without an obvious series of icons to clutter my map, I was encouraged to study it and the world in order to learn how it all worked. In comparison, I am currently playing through Cyberpunk 2077, whose entire city has been accessible since before I even concluded the prologue mission. There are portions of the city I remember, but not necessarily how to get there because I’m constantly following my GPS. Similarly, due to how huge the city and its outer badlands are, I feel too exhausted by the very idea of exploring it all to bother doing anything but use the GPS.

Do I think Cyberpunk 2077 should be more like Elden Ring? Not exactly, though that discussion is beyond the scope of this already monstrous post. Instead, I think it is more accurate to say that Elden Ring, despite being a massive game world itself, is more inviting to the player by keeping the map small and focused just on Limgrave at first. Though the world already looks massive, it doesn’t look nearly as intimidating when viewing that first zone in isolation. By time the map has expanded further and further, the player might have already explored a large chunk of Limgrave and be ready to move on.

Despite being accessible early on, everything about Caelid says “maybe later”.

It’s surprising just how much of game design is based on player psychology as it is on the mechanics themselves. Had the player been able to see the full map of the Lands Between from the start, I don’t think there would have been as much excitement to uncover and explore every corner of the game world. Players would instead have likely suffered some analysis paralysis, less eager to explore the game in full as they saw just how long it took to fill just a portion of the map.

Instead, the map is revealed bit by bit, and each icon pinned on by the player’s own exploration feels like a self-driven discovery. This, again, is psychology. While there is a level of satisfaction to be gained from checking an item off the list, it simultaneously feels as if the player is guided by another’s agency rather than their own. So, having a portion of an empty map slowly filled and expanded upon sells the illusion of being an adventurous explorer more successfully.

This, again, is still just two out of three major elements that contribute to the open-world being so well received. To reiterate, the player is free to choose not only where to explore, but how to explore. Guidance is somewhat provided through enemy placement, the shining rays of grace pointing to locations of importance (many of whom are “optional” but will lead to a separate ending than the “default”), and meetings with Melina and the Round Table Hold, but the player is never restricted in how they choose to make this progress. In addition, the world is revealed to the player in pieces, preventing them from becoming overwhelmed and intimidated by the size of the game world.

The third factor, however, has been spoken of quite frequently in pre-release interviews by director Hidetaka Miyazaki. Throughout the press circuit of 2021, he emphasized the mobility of Torrent and the changes that leaping had brought to the game world, but also stressed the restoration of one’s flasks. Just as the Souls series provides the player with Estus flasks, Elden Ring grants the player flasks of Crimson and Cerulean Tears for restoring health and magic, respectively. In a traditional dungeon, the player has a finite number of these flasks to use between sites of grace. The only method of refilling one’s flasks in such locations is to rest at a site of grace, which would simultaneously respawn all surrounding foes.

The red, wispy trail following my character indicates the foe I just dispatched was the last in a group, restoring one Flask of Crimson Tears with which to heal myself and prolong my exploration.

On the open-world, however, the player is able to restore these flasks by defeating clustered groups of enemies. One might think of them as specific “encounters”, such as a group of soldiers patrolling a road, a pack of wolves running across the hillside, or an ambush of demi-humans waiting for unsuspecting travelers. Any one of these can restore a portion of a player’s healing flasks upon defeat.

It may seem like a small adjustment, but it allows the player to prolong their exploration before needing to stop, rest, and revive all opponents in the surrounding region. Even if the player were to stumble upon a surprise boss encounter on the open field, using nearly or completely all of their restorative flasks in the battle, they can continue with their open-world exploration by simply slaughtering a frail group of zombie-like wretches huddled together by some ruins. Sure, they’ll only get one or two flasks back, but hunt down enough of these easier encounters and you’ll be right back to full capacity in no time.

I truly believe this simple adjustment to the Soulsborne mechanics are a large reason why exploration is able to be so enjoyable for so many. A player can reset themselves to full health and magic without resting at a site of grace, instead cleverly choosing targets on the open-world and rejuvenating their resources back to maximum. This also gives the player reason to engage with the world even when at a high level, as weaker enemies make for excellent restorative fodder.

Which is the most important aspect of an open-world being engaging. An adventurer in the lands between is always scanning the horizon, be it to study the foes cresting the hill just ahead, seeking out potential treasures or landmarks to uncover, or perceive what resources might be gleaned from the flora, fauna, or unfortunate locals unequipped to deal with a high level warrior eager to recover some flasks. It is a world where not an inch goes to waste, players are frequently rewarded, and, most importantly, they are constantly encouraged to engage directly with the world rather than the user interface.

For some players, this is not ideal. They only have one hour of time to play each day and they’d rather not spend it riding into new territory only to discover they are so low in level as to minimize survivability. Perhaps they can only play a few hours each week, and as such they can’t spend hours exploring all of Limgrave and have to bang their head against Margitt or Stormveil Castle if they hope to roll credits one day. Still others may simply get more satisfaction seeing a task list mark their completion percentage of a zone than they do finding a new location, always wondering if there’s something in those starting territories they missed.

More realistically, I think the majority of players are open to both methods of exploration. In regards to Elden Ring, I think it manages to handle the more free, player-driven exploration in a manner that developers truly ought to take note of.

Next time I’ll be discussing the game’s combat.