Ghostwire: Tokyo is Good… for Some People

I can now confirm that the combat to Ghostwire: Tokyo is not as shallow as many reviewers claim it to be. The problem, as I had suspected, is that there’s not enough incentive to make use of protagonist Akito’s full suite of abilities. It is not unlike the original Assassin’s Creed, where any player could rely upon Altair’s counterattack to progress through any combat scenario. It did not matter that there were a slew of other offensive or defensive abilities the player could learn to more efficiently slaughter a group of guards. Why would it? The bare minimum skill was good enough, and therefore the critics – all of whom are theoretically paid to explore what a game is capable of – called it shallow.

It’s not fair for me to push all the blame on writers and reviewers, for they did what most players would do: rely on the most simple, basic strategy necessary for a positive outcome. The blame I lay is for the critics’ failure to fully explore the game and give a more informed opinion than your average poster on Reddit. The problem with Assassin’s Creed is the emphasis on broad appeal, designing a game so that the less skillful players could still complete it with minimal resistance. Ghostwire: Tokyo has done the very same.

I believe it was Steve, my podcast co-host, that was trying to coin a term regarding “minimal viable strategy”; a concept executed to varying degrees throughout games of the past. Do you know how many people can beat Bloodborne, any of the Dark Souls entries, or Elden Ring without capitalizing on status ailments or equipment resistance? Though punishing, From Software specializes in a difficult combat design that makes minimum viable strategies possible. There are also a slew of more complex, highly skill-based tactics, strategies, and builds available, but you do not need them to complete their games. What’s more, the minimal viable strategy still involves studying the enemy’s behavior, dodging, guarding, or parrying at opportune times, calmly striking only when the opponent is vulnerable. This is still more complex than the “wait to press the Y button” minimum viable strategy of Assassin’s Creed, and as a result is perceived as being more deep and rewarding. Despite this minimum viable strategy, however, the game is still difficult enough to incentivize players to explore the deeper mechanics in order to better combat and outsmart their foes.

Ghostwire: Tokyo is not as easy as Assassin’s Creed, but it’s also not as difficult as a From Software game. It sits in this strange limbo where a player must consciously ask themselves if it’s worth exploring those additional yet unnecessary combat options.

If they do, then many of the tasks throughout the rest of the game will prove more rewarding… but is it still enough to make the game worthy of recommendation? That’s a difficult question to answer.

Cash rules everything around me

Let’s take money, for example. There’s not much incentive to walk around collecting cash in Ghostwire: Tokyo if you’re not making use of all your talismans or arrows. As a result, the desire to slip down alleyways or glide across rooftops to collect more money will swiftly be reduced as you find yourself with hundreds of thousands of currency and nothing more to spend it on than cosmetics or music tracks that you’ll barely ever see or use. You could purchase food, but food is so cheap as to barely put a dent in your wallet. This is nothing to say of how freely available food is throughout the overworld, be it in abandoned convenience store bags or mysterious nether-variants of common Japanese snacks and treats. Odds are you’ll find yourself maxed out on most food items within the first few hours of the game.

Money only has a purpose once you’re constantly replenishing talismans and arrows, the former of which cannot be found in the overworld and the latter which is barely provided unless the story necessitates it. This puts the player into a decision-making predicament: use a limited resource that costs money to restore or not? Is it worth using finite and costly tools in an encounter such as this? Or would it be better to just resort to standard means?

This is why I am harsh on critics and claim they have not suitably done their job. To claim the combat is “shallow” is not constructive feedback. The developers have designed their combat system and encounters to take stealthy executions, long-distance archery sniping, and area-of-effect talismans into account, but the only feedback they have is that just firing away while walking backwards from enemies gets stale. Well, yes, they clearly know that, which is why all these other tools are available. The problem is the lack of appropriate incentive (which, admittedly, they are likely aware of now because clearly no one has made use of these tools).

My concern is that the lesson learned will be to make more drawn out tutorials, or change it so that there are foes that are only vulnerable to the stun talisman or cannot have their core exposed without the exposure talisman. In other words, rather than rely on the player to make use of their arsenal as they see fit, forcing the player to use specific weapons or equipment on specific enemies at specific times. This is not necessarily a bad form of game design, but it would remove the freedom of choice and planning that makes Ghostwire’s combat engaging.

Every shrine has one of these prayer boxes that you can drop cash into and receive health, elemental energy, or clues to different collectibles. Why not also include something that restores talismans and arrows, too?

A more subtle way to perhaps steer players into using these items more would be to place ink and parchment at the shrines, allowing the player to create their own talismans without spending money. This creates a reminder within the world that these options exist and that the player may not need to worry as much about replenishing them with a finite resource such as money.

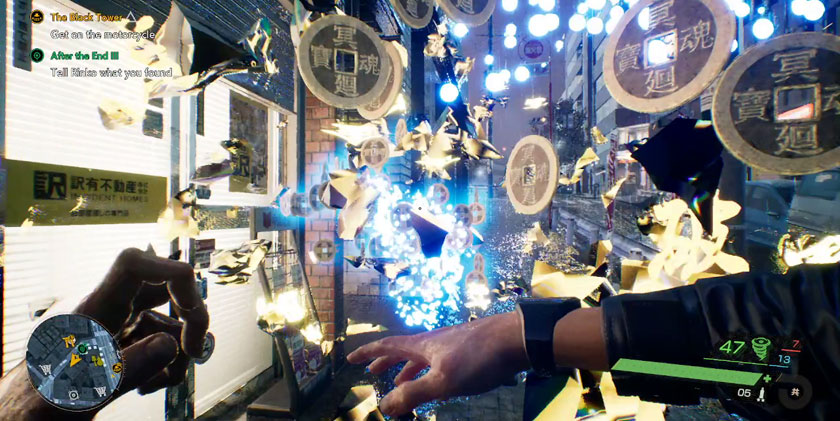

Just as I had theorized in my prior post – which, if you recall, I had written before I had begun experimenting with all these talismans – I found that the real pleasure of combat is in trying to sneak attack or expose multiple cores in order to eliminate groups of foes swiftly. The decoy talisman is useful in these circumstances, gathering many of your targets together in a huddle before launching a stun or exposure talisman together, or charging a fireball and launching it into the crowd. What would have been extended, boring encounters of backing away from foes while rapid-firing the wind elemental power have now become swift skirmishes where the majority of mooks are eliminated immediately.

Where the talismans helped the least were the mandatory encounters filled with waves of already aggroed foes. Decoy was ineffective against already aggressive enemies and therefore made bunching them together more difficult. Stun and exposure talismans were still useful, but without knowing how many waves you’ll face or what powerful opponents lie ahead then each talisman remaining in your inventory becomes more and more precious. The thicket talisman is similarly only useful if the player is trying to be stealthy and therefore has no use in an already frantic fight. Arrows are slow and near useless once enemies have been alerted, which makes the “hangman” spirits particularly frustrating. I believe those monstrosities are vulnerable to headshots, but they move so quickly and have such volatile projectile attacks that “mastering” their encounters is a general pain in the rear.

Once more, however, this still depends on how many talismans the player has stocked up on, and whether they’re willing to part with them. As soon as you enter a story mission or side quest, it’s possible you’ll find yourself pushed through multiple encounters with no store in sight. This means any non-elemental resource you spend is gone until the quest is over, leaving the player to decide whether to use or save their talismans and arrows. Given how much of a running joke it is in the JRPG community to save your cure-all items until the final boss, only to never use them in the final encounter, I’d imagine most players will just end up holding onto their tools and relying on that minimum viable strategy instead.

A well-placed Stun talisman leads to an opportunity for either an Exposure Talisman or a Fireball. Either way, it’ll make quick work of this crowd.

Now, I’ve spent a lot of time discussing combat so far, and I think that’s because I didn’t really like it until I began to experiment more. Once I started using all the tools in Akito’s belt I found combat more rewarding and was more likely to engage with the spirits and ghosts loitering Shibuya’s streets. It’s also the one aspect of the game that is easiest to break down what is and isn’t wrong with it.

When it comes to everything else, however, that’s a little more difficult because it really is the most subjective aspect of the game. I don’t like most open-world titles, and I especially favor games like Breath of the Wild or Elden Ring where you’re not chasing icons across the map. In fact, I’ve come to realize that my preference is to be given an empty map that I fill with icons. There’s something more satisfying in seeing the vague shape of a thing etched into the topography, voluntarily venturing off to explore what it could be, and then having a name and identity attached once you’ve arrived or plundered its treasures. The icon becomes a memory of a discovery rather than the next stop on your errand list.

Ghostwire: Tokyo, on the other hand, is the opposite. It’s not necessarily completely filled with icons – there are some things that don’t show up on the map – but it certainly has a grocery list of activities for you to complete. Theoretically, I should dislike Ghostwire: Tokyo because it has so many traits that I’ve come to dislike in the open-world “genre”. Instead, I actually enjoy the game and find its take on the open-world mostly relaxing.

That’s an absurd amount of icons on that map.

It could be that I’m coming off of over one-hundred hours of tense and sometimes frustrating exploration in Elden Ring, where death was common and setbacks frequent. In contrast, Ghostwire: Tokyo is a welcome world of absolute chill, where conflict could be avoided in favor of climbing to some rooftops and snatching some spirits. However, I also think it’s because Ghostwire is a smaller, densely packed world as opposed to a sprawling continent miles and miles long and wide. Most open-world games focus on being absolutely massive, but here the district of Shibuya is comparatively smaller and quick to cross. This not only prevents the player from being overwhelmed by the laundry list, but makes it easy to simply jump from one objective to the next.

I discussed this last time as well, but I think there’s something appealing about a smaller world you can just stroll through and accomplish things within. If I could turn combat off, I’d simply wander the world collecting spirits, spotting hidden tanuki, smashing money pots, and snatching up valuable trinkets desired by the many cash-hungry cats strewn throughout the city.

Is it a good open-world? I honestly don’t know how to answer that. On one hand, I feel like each activity has some sort of a purpose. Spirit rewards are converted into experience which allows you to increase your combat capabilities, and money allows you to purchase healing and talismans. Side quests, tanuki spotting, and trinkets all contribute to these rewards that then feed into the gameplay. Is there simply too much, however? Are there too many spirits strewn across this small world? Too many trinkets? Are there too many combat encounters?

For me, the answer is “not really”, but it’s because I’m not engaging with Ghostwire: Tokyo in the same way I engage with other games. For me, Ghostwire: Tokyo is a chill, relaxing, satisfying collect-a-thon broken up by occasional combat scenarios. When you combine my combat strategies with the swiftness of most open-world activities, I’m not spending too much time on any one thing. I’m getting a steady dopamine drip whilst my mind is engaged through the navigation of the world and the swift dispatch of foes from hidden positions.

Apologies for the blurry image, but did I mention how great it is to just conjure a Tengu out of thin air and grapple your way onto different rooftops? It’s probably one of the best abilities you could unlock in the game.

How does one recommend such a game, then? To whom do you recommend this game? I’m not quite sure how to answer that. If we look at the games I compared Ghostwire to last time, I’d say it is overall better than Gravity Rush, but the heights of Spider-Man’s gameplay are superior. That said, Sony’s Spider-Man also frustrated me far more frequently. Ghostwire: Tokyo has the edge for me, personally, if only because I had far fewer gripes with the experience than I had with Spider-Man.

There is value in that, I think, and it is what encourages me to defend this game more than it probably deserves. I want to make it clear that this game is not great, and my entire thesis last time was that the game is good enough that it does not need defending. I still stand by that statement, yet I feel compelled to defend it nonetheless.

If you are going to assemble yourself an open-world game that has a laundry-list of activities to complete, I’d rather you do it like Ghostwire: Tokyo than any Assassin’s Creed or Far Cry title. It is a smaller but dense location whose collectibles all fulfill a purpose of progress, uniquely interpreting the lore of the world with combat unlike other gaming contemporaries.

I can’t promise this game is worth the full $60 for you, but I certainly believe the game is worthy of more positive attention than it seems to be receiving.