Grind Quests

Some years ago, back when I was still in my twenties, I had discovered all of my efforts to grind in EarthBound had been a waste of time. During my youth I thought the occasional level in which only one or two stats would see an insignificant boost was just poor luck. During my adulthood, however, I realized that any significant level gain typically coincided with a large jump in required experience points to reach the next level.

Rather than pace back and forth in specific dungeons and hazardous areas, coaxing foe after foe into a brawl so that I might slowly climb towards greater feats of strength, I decided to… just play the game. To progress linearly, tackling all foes that came my way and gritting my teeth in preparation of getting my flattened posterior handed back to me inside a Mach Pizza box. While my first assault on the arcade and climb up towards Giant’s Step – the first dungeons of the game – were a bit more troublesome than usual, EarthBound typically leveled me up to the strength necessary to take on each location’s challenges. The experience rewarded for defeating enemies was already calculated by the developers to match the amount required on an unknown “table” that defined the ideal level for each section of the game. While a player could certainly grind in a dungeon’s entrance for a few levels, they’d fail to gain many – or any – substantial new levels on their way towards the boss.

As I progressed towards the game’s end, I found my characters and their levels were approximately the same as I’d grind them to in prior playthroughs. I always found the game to be so challenging that you “needed to grind”, but the reality was that the game minimized the benefits of grinding in order to maintain a challenge. It would require an immense amount of patience – an amount I certainly did not possess as a child nor had the time for as an adult – to perceive any benefit.

It was this experience that encouraged me to approach all my prior childhood role-playing games without grinding. No more pacing back and forth in forests on the overworld map, sailing across the world to the perfect spot with the most rewarding foes to fight, or sticking to the ideal corner of a dungeon to get some farming in. The more of these games I play without grinding, the more I realize I never needed to do so. At best I’d simply be overpowered for one or two dungeons, gaining almost nothing until smacking right back to where I was supposed to be. Alternatively, avoiding the grind encouraged me to explore each game’s mechanics more deeply, developing a deeper appreciation for its design than I had before.

For this reason, I find The Witcher 3 and Xenoblade Chronicles’ “solution” for grinding interesting yet flawed, while having a begrudging appreciation for Yakuza: Like a Dragon’s inclusion of this trope in an arguably efficient manner.

Both The Witcher 3 and Xenoblade Chronicles reallocated the greatest quantity of experience gained from combat to quests. If you wish to level up, you better go crawling through town and finding quest givers or job postings so that your experience can skyrocket. (As an aside, I am aware these games are not unique or are the first to do this, but they are the two games I’ve played most recently that brought this topic to mind. As such, I’ll be discussing them exclusively.)

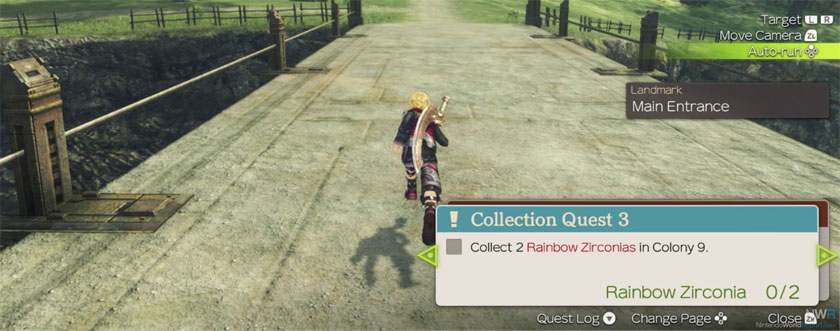

In the case of Xenoblade, side quests were the primary method of gaining experience due to the inspiration taken from MMORPG’s. The difference is that MMO’s require you to grind in some fashion so that you are encouraged to keep playing, and therefore keep on paying that monthly subscription. Xenoblade Chronicles is a single player experience that allows the player to gain those levels and improvements at a far faster pace.

Exploration of the game world is also a source of experience for players. Every landmark discovered and corner of the map uncovered had the potential to award the player with an abundance of points necessary to boost some levels, advance their skills, or increase benefits gained through bonds between party members.

Unfortunately, the quests themselves are about as shallow as you’d expect for an MMO imitation. You’ll be tasked with hunting down specific monsters, often in the hopes they’ll drop a specific piece of loot for you. Just like all MMO’s, you’ll never need just one of these items. Only on rare occasions do these quests provide a deeper look into the many locals of the world’s colonies, and in a handful of cases will require the player to choose one of two outcomes. These may sound as if they could provide depth to the world, but the presentation itself feels cheap and shallow. Character models are often copy-paste and therefore lack individuality.

There are some quality-of-life adjustments that prevent this process from being as tedious as it could be. The game will immediately mark most quests complete once the desired materials have been gathered or the requested task completed. There are some exceptions that require the player to return to the quest-giver, but these are less common. The game also provides the player with the ability to manipulate the in-game clock in order to brute force certain weather conditions or adjust the time of day in order for certain creatures or quest givers to appear. This, however, highlights that restricting such quests to time of day or certain weather is bound to frustrate players, and therefore requires an in-game clock manipulator to reduce the tedium. Keep in mind the Definitive Edition also added in map markers for quest requirements so that players could find the materials, creatures, or characters more easily.

The player may not be busy pacing the overworld, hacking and slashing at every creature that crosses their path, but must still wander aimlessly between zones, checking the map to see if any objective markers show up. Even if they don’t, the player then must hop into the menu, change the time of day, and then check back on the game world and its map to see if anything has changed. If their quest target demands a specific weather effect, they must continue to turn the clock in one hour increments until the game decides to roll those clouds or that heat in. Never does the game world truly achieve any greater depth. The player is merely accomplishing errands for the game designer in hopes of getting stronger.

The Witcher 3, then, should be a notable improvement. Every side quest is designed to have compelling dialogue; a fascinating snippet or short story told within the greater epic. The way most players tell it, the experience gains and rewards are only the secondary reason to be chasing down these errands for the locals. Top notch and unique narratives are the other.

This would assume that all side quests are created equal – at least, in terms of length and writing quality. They certainly are equally oppressive and pessimistic, constantly reminding the player that there’s no such thing as a “good choice” in Geralt’s line of work. While I can appreciate games and narratives acknowledging the difficult moral quandaries of reality, it becomes somewhat depressing to be constantly reminded that humanity was the real monster all along. Fitting for a novel or film, but bound to be a concept stretched thin if hammered too harshly throughout an entire book or television series. To do so for every quest within a game? I sure hope CD Projekt Red aims to pay for my therapy bills afterward.

The quests aren’t just formulaic from a narrative or tone perspective, either. They largely revolve around Geralt loyally following his detective vision like Toucan Sam follows his nose to a bowl of Froot Loops™. Rather than sniffing out sugary confection masquerading as a healthy breakfast, the player will be tracking down a beast, a monster nest, a corpse, or, on rare occasions, a still living person. Don’t worry, they’re probably not long for this world, and odds are it’ll be the player that separates the head from its neck. Swing sword, cast some Igni spells, throw in a Quen or Yrden for some spice, and then collect your reward. Garnish with someone’s life forever being ruined in the process.

While the mechanical and tonal repetition of Witcher 3’s side quests would diminish my appreciation for the scale of its accomplishment, it is the diminishing value of each quest’s reward as you level up that begged me to question “why bother?” CD Projekt Red bombards the player with a variety of quests at every possible hovel you could stumble into, no doubt in an effort to ensure the player is sufficiently entertained no matter which road they choose to travel. The problem is that the player will swiftly begin to out-level every quest collected in any given region, and perhaps even outpace the regions ahead. Side quests will continue to be dumped upon the player’s plate, but just as over-consumption of food has diminishing nutritional returns, so too does the completion of each quest. In time, the amount of experience gained for finally answering the call of a poor peasant farmer is worth less than that obtained for beheading a group of drowners by the river – and that’s a pretty insignificant amount.

This defeats the purpose of using quests as your primary experience provider over combat. It makes sense that an experienced warrior would not learn or gain much from slaying an easy foe they’ve fought plenty of times before, but if you wish for the player to gain levels through quests instead of combat, then you should perhaps refrain from drowning them in a horde of side quests for fear of the player getting bored. Or worse, feeling pressured to simply include “more” as if quantity somehow equates to quality.

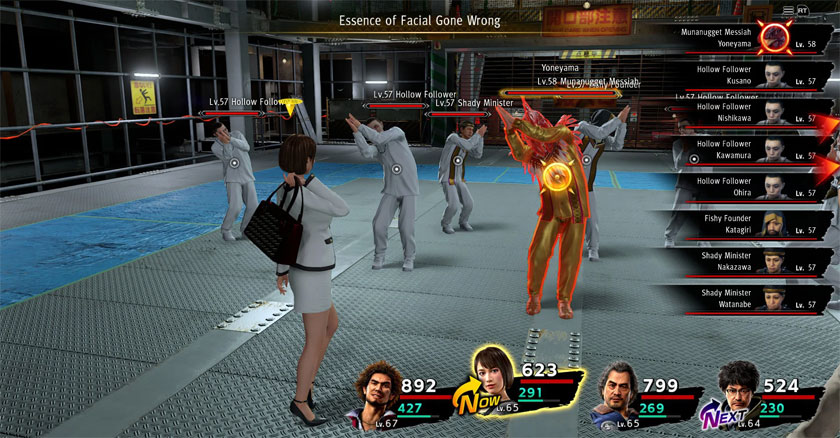

Perhaps this is why I had some silly degree of respect for the Battle Arena in Yakuza: Like a Dragon. It is deceptively introduced as an optional block of content, a marathon of fifty floors of combat challenges that the player can tackle all at once or in ten-floor increments.

While the game makes it seem like this is an optional arena, the next step in the game’s narrative will have leveled up foes and bosses far higher than the prior zone. The game expects the player to stop and complete this arena because… well, this is the part of the game where most JRPG players stop and grind, right? About to head into the viper’s nest! Everything is about to get crazy difficult! Time to grind it out, learn some new skills, and get stronger!

It’s a strange yet fitting meta-observation on both the shounen stereotype of the training arc and how players will pause and grind before jumping into a difficult or final dungeon. The battles are sufficiently challenging, have conditional goals in order to boost potential rewards, and are guaranteed to shoot protagonist Ichiban and his comrades up around ten or so levels. It’s very brief and condensed, and ultimately doesn’t take much time to progress through.

Nonetheless, it still halts all forward momentum the narrative has developed, forcing the player to instead screech around a corner and distract themselves with an activity that exists for its own sake. Admittedly, it is somewhat fitting for the game given Ichiban’s obsession with Dragon Quest. The retro classic impacts his perception of the world and his role in it in such a fashion that he would certainly be influenced by the tradition of “the grind”. The battle arena, then, is a condensed process of the grind, reducing it to a single, brief, compact series of skirmishes. The player can earn greater rewards, such as powerful weapons and accessories, by completing optional objectives and tasks within each bout.

It’s almost genius, frankly, to both acknowledge the trope and player expectation of grinding while executing it in a fashion that minimizes its invasive nature to the game’s flow. Nonetheless, it is still invasive and awkwardly placed. This chapter isn’t the final one, after all, and all prior chapters of the game felt far more balanced. Even if I comprehend the reasoning for the arena thematically and mechanically, it still feels oddly placed and presented.

If I had to choose, I’d prefer the Like a Dragon approach to the grind. It may be disruptive of the game’s flow up to that point, but it’s also only disruptive the once. Xenoblade Chronicles may have had brief side quests, but they were so numerous, scattered, and sometimes difficult to track down that they ultimately caused a lot of time spent doing nothing of value. The Witcher 3 has some real delightful side quests whose writing is top notch and unique, but the vast majority follow very similar templates and are so numerous as to inevitably become worthless in the long run.

At the same time, this is strictly viewing side quests from an experience gaining and grinding perspective. Yakuza: Like a Dragon is also littered with side quests, it just happens that they don’t often reward experience to the player.

Perhaps one day I’ll do a comparison between these games and the style, variety, and abundance of their side quests. For now, however, I’ll simply conclude that replacing grinding with side quests can be better than demanding the player pace back and forth on the overworld. You just need to make sure that time is spent efficiently. If we’re seeking alternative methods to grinding, however, Yakuza: Like a Dragon’s brief digression is far more preferable to me.