Metroid Dread is My Game of 2021

It came close. It came really, really close in terms of my favorite release in 2021. At first glance, Metroid Dread doesn’t seem to do nearly as much as Resident Evil Village in terms of honorary “favorite of a whole year” status. The latter has a far greater variety of set pieces and gameplay, higher production values, and the upgrades and unlockables make for a better incentive to replay the game than Dread’s selection of artwork.

This is also why it is understandable that others might choose Resident Evil Village themselves. What I’ve learned discussing the latest Metroid title with others is that it has very specific goals in mind, and those goals don’t appeal to all fans of the franchise. Village, on the other hand, more broadly caters to a variety of players, regardless of whether they’re a franchise fan or not. Even if the focus on action has increased from the previous entry, it is better balanced between different set pieces and locations. Horror fans can experience more harrowing or terrifying moments; some environments are linear and straight-forward or amusement park in style while others focus on that puzzle-box building of the original entries in the series; there are also plenty of treasures, collectibles, and optional bosses for fans of exploration to discover.

On paper, Metroid Dread is a really good game, but has less to offer in comparison. However, there’s a lot of stuff going on underneath the hood here that, for players of a particular nature, not only begs a return to its extraterrestrial world of ZDR, but to further master and improve on one’s abilities. It is for this reason that Metroid Dread inches its way past Resident Evil Village for me, earning the crown of my favorite game released in 2021.

Admittedly, this is not the side-scrolling Metroid game I had envisioned as my “perfect” sequel. Looking back on my video analysis of Metroid Prime: Echoes, I discussed my thoughts on how one might improve the map design for both a 2D and 3D Metroid game. The ideal solution I had proposed is to create a central “hub” region which allows for multiple routes and shortcuts between each zone, as well as linking each zone together directly where possible. It’s a nice idea, but is easier written on paper than it is implemented in a fully functional game. Nonetheless, when I created that video, I held the belief that any game relying on tools such as quick travel was either insisting on building too large a world to sustain the genre’s explorational concept, or failing to properly connect its disparate zones together in a skillful manner.

Now, having played far more Metroidvanias and experienced Dread’s own use of fast-travel in points, I better understand the purpose. In fact, I was initially disappointed by each zone in Dread being separated and self-contained. Was it really so different from Metroid Fusion splitting its different zones apart from one another? I can confidently say that it is. The inability to physically lock each zone together is more a technical limitation than it is a design flaw, and it has existed even in Super Metroid, which itself relied on elevators to connect the separate sectors to one another. The game needs to swap textures and assets in memory based on which zone you are present in, and therefore the elevators, transports, and even teleporters are workarounds to link zones together while allowing for a loading screen, just as the elevators served in Metroid Prime on the GameCube. What Dread avoids, however, is creating specific fast-travel points that link to a central hub point, or that cycle around to other fast-travel stations in a loop. Dread still relies on the player studying the map or memorizing the region’s layout in order to make their way around. In other words, each sector has multiple connections to its surrounding sectors, generating more points of access for back-tracking and navigation around the world.

From here, we can begin to see the evolution that side-scrolling Metroid’s map design has taken. In Super Metroid, the player would occasionally be locked onto a forward path. The first time you descend from Brinstar towards Norfair, the player is unable to pass by a gate without the Wave Beam, or to ascend a pit without the Ice Beam and High Jump. This lock had prevented players from getting lost in a new zone, forcing them to seek out every hidden passage or destructible block to obtain all necessary upgrades and to find the critical path forward. Had those doors behind not locked, then the player would have been able to backtrack far more of the map and possibly increase the time spent trying to figure out the path forward.

Metroid Fusion removed the organic nature at which these locks would appear by modifying the world to (often permanently) close the route behind them, or by literally locking all other doors to set the player on a singular path. The A.I. companion Adam is narratively responsible, locking all doors but those that lead to the objective marker he desired to place. One could perceive this as a potential thematic choice, representing how limited Samus feels with a stripped down suit and her powers robbed from her. The game does open up more as Samus gains more powers, objective markers becoming more vague or relying on the player figuring out the route forward on their own. Once Samus has obtained the final Screw Attack ability upgrade, however, Adam will completely lock the station down. Only the path towards the final confrontation and conclusion will be permitted, despite the fact that the player is now capable of finding and unlocking a variety of collectible power-ups scattered throughout the game world. The player cannot hope to 100% Metroid Fusion without already being aware that they must avoid accessing data rooms, going so far as to obtain one specific power-up last: otherwise, they’ll be forced to step into one of the aforementioned data rooms and lock access to any missile packs, power bombs, or energy tanks scattered elsewhere.

As a result, one of Fusion’s main features – the ever-changing world – felt more like a detriment to players used to Super Metroid’s comparatively more free-form exploration. Metroid Dread takes that notion of a changing world and executes it in a manner more in common with Super Metroid’s progression locks. Just as a player could only backtrack so far in parts of Super, the player can only wander set portions of the environment after progressing so far in Dread.

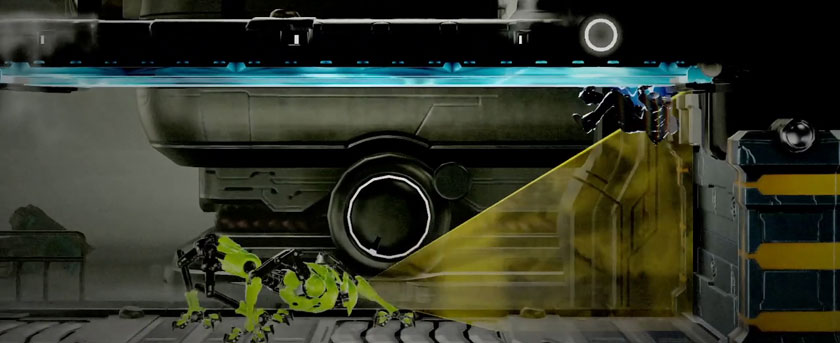

The cloaked beast slithering into what looks to be a drainage pipe is the first major boss of the game, and is here foreshadowed to the player for the second time as they progress through a hallway they’ve gone through before. The cloaking ability obtained from the boss will be necessary to pass through the door Samus is currently leaping away from.

For the most part, this change in the world’s design is not a problem. It is often used to foreshadow incoming bosses or to illustrate how the world is responding to Samus’ presence. We see this early on in the starting zone, where the player will completely loop back through their progress only to see hints of a monster slithering through the background. The game is simultaneously informing the player that they’ll not only be able to open more and more pathways with each power-up they’ll gain, but also that the world itself may not necessarily be the same next time they go through a hallway or room.

If the player is simply looking to push forward on the critical path, following the map onwards towards the next upgrade or boss fight, then the map design and the changing world guide them through masterfully. After obtaining certain abilities, the player will be placed directly where they can use said ability to open doors or break through walls which lead right to locked doors or passages they previously had to pass on by. It not only helps first-time players make their way to the next objective without being directly instructed to do so, but it keeps speed-runners from wasting time wandering from one corner of the map to the next.

Which reveals the higher priority of Dread’s design team at MercurySteam: to design for speedrunners before you design for explorers. I’ve played through the game multiple times now and have collected all items on the map twice, and each time I found back-tracking through certain zones to be a bit of a pain. Some of those environmental changes cannot be undone, and several passages will forever be locked. This means what looks to be an optimal route can instead be an impossible route, forcing the player to find a more roundabout pathway to get to a specific portion of a zone. Some harder-to-find shortcuts can be unlocked, but often from one specific direction. This means if you’re hunting for any missile packs or energy tanks you passed by on the trail, you might approach from the opposite direction necessary to open the path forward.

This is why I think there are some players that have found Dread more frustrating. For me, personally, the only region that is truly bad with this sort of design is Ghavoran, but it can certainly happen elsewhere on planet ZDR; especially if you’re trying to hunt down items before you’ve approached the final stretch, where many pathways will remain locked until you’ve retrieved several late-game upgrades.

Moving this mechanical block forward is required to progress, but you permanently close what could be best route back to Ghavoran’s elevator from most other zones. MercurySteam should have considered placing destructible blocks that the player could Power Bomb or Screw Attack through to create an alternate shortcut for late stage exploration.

I imagine this would be less of a problem since both Metroid and Zelda franchises benefit most from saving the globe-trotting item sweep for the end-game, but Metroid Dread is also the most difficult (2D) entry in the franchise thus far. Though Samus is the most mobile and acrobatic she’s ever been, her every movement silky smooth in response to player input and surpassing all other Metroid games to come before, she’s also pitted against equally swift and deadly foes that are far less forgiving than prior bosses and beasts. Even when a bosses’ pattern is clear and repetitive, there may be tight timing and specific responses required in order to avoid each devastating attack.

For most skilled players, there are enough items scattered across the critical path to keep the player well stocked. In fact, speedrunners can easily obtain almost as many health tanks as players taking time to peer into and spelunk every corner of the world, only falling one or two behind before the game truly opens up towards the end. This means any player having a rough time is unlikely to go back and get as much assistance from health boosts or an expanded arsenal of missiles as prior entries, leaving them to “git gud” by learning not just the patterns, but the timing required to dodge and strike the colossal creatures.

What most players may not realize is that there is more than one way to skin a cat in Metroid Dread. The most obvious shortcut to defeating the bosses is to keep an eye out for moments to counter-attack, but upgrades such as the speed boost will allow them to inflict incredible damage that can do as much as half the length of a battle. This is also true of enemies out in the world, where sometimes it’s better to just swing your counter while sprinting forward to kill or knock an opponent backwards, or to keep holding onto the charge beam while spinning through the air to kill weaker foes.

Which, I think, is why I myself find the game so incredibly satisfying. No doubt this write-up does not sound like the incredible praise you’d expect of my favorite game of the year, but it’s also an examination of how Metroid Dread is an evolution of the franchise direction rather than an attempt to recreate what Super Metroid had already done. After five or so runs through Metroid Dread on both Normal and Hard mode, with full completion on both difficulties and a speed run on Normal, I’ve begun to discover more and more efficient ways to sprint through its corridors and tackle or skip by the monsters populating the depths of ZDR. I’ve seen many players and writers lament the number of familiar and “safe” power-ups that the game provides, but I don’t think they quite grasp the more subtle ways in which Dread has evolved as its own thing, separate from the direction of the rest of the Metroidvania genre.

This is just one of several bosses whose fight can be shortened through use of the Shinespark Dash.

Let’s consider that Metroid Dread is the first entry in the whole franchise to start in the depths of the planet already. Rather than land on the surface and dive deeper and deeper into a steadily more threatening world, Samus is climbing up higher and higher in order to reach her ship. Rather than immediately grant the player the morph ball and power bomb at the start, the player is left to explore without those franchise crutches for a while, familiarizing themselves with the physical prowess of Samus’ acrobatic abilities. Certain opponents early in the game rely more on the counter ability, but it can still be used to quickly annihilate others or to knock certain larger beasts backward so that Samus can unload her arm cannon upon them.

With Resident Evil Village, I am having a lot of fun playing it, but I’m not really discovering more tricks or mechanics each time I run through. There’s no doubt that there is more to discover, but on my fifth playthrough I only found one overlooked trick for a boss. Otherwise, it was mostly the same experience as before. With Metroid Dread, I feel as if I am still noticing and observing new things, be it in terms of game mechanics, tactics, or simply the manner in which the world is designed to steer and guide the player a certain way.

This is most true with perhaps the most controversial inclusion of the game: the persistent E.M.M.I. robots. They are quite a hassle on a first playthrough, especially when a player is unfamiliar with the environment they’re about to jump into. In truth, they actually are not that difficult to outsmart or avoid, and the more tricky an E.M.M.I. becomes the more exits their zone has to act as a checkpoint. So, even if an exit leads directly to a dead end, it allows the player to restart from a door closer to their overall objective.

Which makes the E.M.M.I. a unique factor, regardless of whether you’re attempting a speedrun or just making your way through on a normal replay. Not unlike Mr. X in Resident Evil 2’s 2019 remake, the optimal routes and tactics of a player are tested with a persistent opponent that cannot be killed by conventional means, and whose A.I. the player must adapt to in order to proceed forward. The E.M.M.I. each follows specific rules that can be exploited or worked around, but it takes experimentation, trial, and error on the part of the player.

Which is, perhaps, why I’ve come to love their inclusion more and more. With each new run through the game I’ve found myself caught and defeated by them less and less, even as I find my memory of their zone and the critical path forward foggy. Which, perhaps, also acts as a sort of representation to my experience with the game as a whole. I have found myself good enough that I don’t mind playing on Hard as my default experience. Enemies hit far harder and bosses are more lethal, but I have been encouraged to perfect my play and learn better tactics for each fight.

To put it another way, I am continuing to carve a more optimal path through Dread’s world, which is what has always made the Metroidvania franchise so appealing. It’s not just the exploration, it’s optimizing your routes to be better equipped for certain battles. It’s a genre built on mastery and perfection, where a single playthrough is only able to deliver a portion of the intended experience. Given that I’ve developed a philosophy of replaying games in order to better learn their mechanics and what makes them tick, it is no wonder that I have grown steadily more fond of the genre.

Yet, just as before, Metroid Dread has illustrated why Nintendo’s franchise that has helped birth the genre remains best in class for me. From how it feels to control Samus, to all the little tricks and tactics that the game allows you to discover on your own, to how perfectly it guides the player through its world, Metroid Dread is a game custom built for me – or so it feels. I absolutely love it, I’m still not bored of it, and I don’t know when I could become bored of it.

I can only hope that Metroid Prime 4 can deliver as perfect an experience, though perhaps more focused on the slower, ponderous, exploratory traits that the 3D games were best at.