Toren

Toren is an indie game best viewed like a short-film. Like Portal and Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons, it is an experience that only takes about two hours to complete, perhaps even less. However, it’s not really focused on exploring novel game mechanics like Portal or Brothers are. It’s much more interested in delivering a narrative.

Toren is an indie game best viewed like a short-film. Like Portal and Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons, it is an experience that only takes about two hours to complete, perhaps even less. However, it’s not really focused on exploring novel game mechanics like Portal or Brothers are. It’s much more interested in delivering a narrative.

This is perhaps due to the clear lack of a decent budget, or maybe the limited scope of the development team. Based on the credits, there were only about six people tops doing programming work, with the rest dedicated to artistic or producer roles. As a result, swinging your blade against the nasty little scrappers that occasionally pop up around the game’s Tower feels an awful lot like slicing air. There’s no feedback provided, be it a vibration of the controller, a shriek of the beast, or an effective pop upon defeat. The enemies just puff into dust, almost as if their very cellular structure collapses right then and there.

While physical movement is at least more effective, our protagonist feels a bit slow to wander the environment. Pressing down on the analog stick is a lot like hitting the gas in a smart car to climb a steep hill. You might eventually make it to the top, but gravity is fighting you the whole way. It’s a feeling to adjust to, and I imagine the feel is partially due to the floaty nature of some of the character’s animations.

What is most peculiar is that the camera’s movements are tied to the character’s. If you want to look behind you, in most situations you’ll have to physically turn around. The right analog only slightly adjusts the camera along the vertical and horizontal axes. Movements are also rather imprecise, seeming to only follow eight general cardinal directions akin to older N64 games.

None of these factors impact the game too much, as it otherwise accommodates for such limitations. Leaps are extended as far as they need to be to reach your destination. Paths outlined in salt only need to vaguely resemble the intended shape. The camera shifts so that it can direct the player right onto the desired path, rather than risking them falling from the tower.

Despite the limited budget, the game is quite effective at directing the player where they need to go. The only real hints are button prompts over interactive objects, many of which are key to solving puzzles. Largely the puzzle challenge is around the Legend of Zelda style “light the torches to reveal a secret” level of difficulty, but some confrontations or obstacles are a bit more clever. Visual cues or simple button experimentation will often reveal the trick to any problem, keeping progress moving at a steady momentum.

That very momentum helps make the story feel more whole than you typically get with the more episodic, on-and-off nature of gameplay. Sometimes the final level or battle rarely has that climactic tone to it in a video game, but here the experience is so fresh in your head due to being so brief that it truly feels like a culmination of sorts. All previous conflicts with this dragon come together, fusing with elements of the narrative to deliver an effective conclusion.

The game feels like an interesting proof of concept. To make a comparison to Hollywood, I feel like this could become a greater budget title in the same vein as Alive in Joburg later became District 9.

The game feels like an interesting proof of concept. To make a comparison to Hollywood, I feel like this could become a greater budget title in the same vein as Alive in Joburg later became District 9.

Though there’s not much reason to really play this game again, not for the mechanics at least, I certainly want to jump back in again to further analyze its themes. Note that, from here on out, I’ll be diving head first into spoilers for the game’s narrative. If you are interested in playing the game and want to go into the story cold, I recommend stopping here. I’ve said all that is necessary for the gameplay.

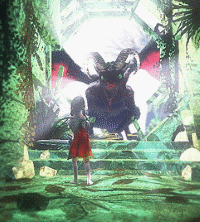

From what I can gather of the game’s narrative, a magician had sought to build a tower towards the heavens, bounding men to help him reach such heights (if you’re reminded of the song Stargazer, then congratulations, you and I can be friends). The sun had become angered, and for whatever reason the Moon had been taken from the sky and personified into a young woman. This is where I’m a bit unclear as to the specifics. The sun is angered, but the sun did not send the dragon which now torments the tower. The Moonchild, our protagonist and the player’s avatar, is seeking to defeat the dragon. At this stage, time has stopped due to the lack of a day and night cycle, and humanity seems to have perished, or at the very least is tormented by never-ending daylight.

That’s about all I can gather. The Magician, or his spirit at least, advises the Moonchild and tells her tales of the tower and its prior inhabitants. In these stories he speaks of a warrior named Solidor, who, according to the game’s website, was sent by the sun. Solidor tries to defeat the dragon, but is unable to do so on his own.

I believe the key theme here revolves around the word “cycle”. Everything about this game comes back to a cycle of some form. At the very beginning, the Moonchild is slain. Upon her death, a new Moonchild is born, swiftly growing into adulthood. Note that the moon itself has cycles, frequently going in and out of different visual phases. An individual’s lifecycle can easily be represented by phases of the moon, and vice versa.

Of additional note, a moon’s cycle from new moon to new moon lasts around 29.5 days. Each cycle takes about a month. Whenever our Moonchild awakes into a new life or wakes from a dream, she is found in what looks to be blood. In many of her dreams, there are pedestals containing blood upon them. There are also two moments within the game where the player must take the life of a creature, sacrificing it. I cannot say for sure, but I’m curious if this acts as a metaphor for a woman’s monthly menstrual cycle.

After all, this is very much a game about cycles of life, and the Moon is being represented by a female. The menstrual cycle is tied to a woman’s ability to create life, and happens about as often each month as a new cycle of the moon’s phases.

Regardless of intentions there, the final conflict requires the Moonchild to work alongside Solidor, a warrior sent by the sun. Each character takes turns guarding the other from the dragon’s attacks, and even take turns on the offensive. Just as the sun and moon change places between day and night, the player and their companion must swap places during the final conflict.

Regardless of intentions there, the final conflict requires the Moonchild to work alongside Solidor, a warrior sent by the sun. Each character takes turns guarding the other from the dragon’s attacks, and even take turns on the offensive. Just as the sun and moon change places between day and night, the player and their companion must swap places during the final conflict.

Upon completion of the game and defeat of the dragon, the Moonchild resumes their existence as the moon itself, and during the final credits sequence observes the history of mankind. The changing landscape of war is observed until all of humanity is nearly wiped out, the reset button struck, and a magician once again seeks to build a tower, beginning the cycle anew.

My first impression of the game was that this game was likely a retelling of a local myth to the developers, located in the country of Brazil. However, I have to wonder if there is more going on than merely recreating a legend. It certainly feels like an interactive mythology, but the cycles give it a greater purpose and theme to its design.

Either way, even if the game’s mechanics are certainly indicative of the lower budget, tying so many themes into the gameplay has left an impression. It will unlikely be the best game I’ve played this year, even amongst independent titles, but it will certainly be a unique one begging for me to revisit it.