Travis Strikes Again: No More Heroes

My interest in Travis Strikes Again diminished once its gameplay had been revealed. The preceding two titles of the No More Heroes franchise lack mechanical depth, but they possess a blistering pace of violence punctuated by bloody dismemberments and suplexes executed through simplified motion controls. A differently stylized version of DOOM’s Glory Kills, preceding one of the shooter’s defining features by almost a decade.

That stylish satisfaction looked to be missing in Travis Strikes Again, replaced by the top-down hack-and-slash antics more reminiscent of Gauntlet than the frenzy of Devil May Cry simplified. While I like to try and receive each type of game openly – even spin-off titles like Metroid Prime: Federation Force – the less hectic game style just had far less appeal to me.

It was only after seeing the thoughts and impressions of a few YouTubers I follow that my curiosity was once more piqued. Many on Twitter had observed Travis Strikes Again to potentially be game director Goichi Suda’s most personal work. TheGamingBrit’s deep dive on the game would push me towards a purchase. I became determined to see for myself what sort of auteur work was hidden within this low-budget follow-up to a game franchise forgotten by mainstream audiences.

What I found was certainly a personal work, but one whose most interesting content is tainted by the far more oppressive presence of mediocrity and self-indulgence.

Travis Strikes Again is not so much bad as it is bland; a curse upon a franchise whose greatest selling point has been its style. The player’s combat capabilities are largely filled out by a variety of special attacks that each run on cooldown timers, engaging the player enough to be thinking some degree of strategy while hordes of enemies close in around them. Unfortunately the game’s enemy and encounter design fails to properly encourage the player to experiment with the various special abilities they’ll discover on Travis’ adventure. This makes it all too easy for the player to stick to what they know, relying on the same basic strategies and button prompts from start to finish rather than having their skills and adaptability tested in new and challenging ways throughout.

Part of the problem is that many of the opponents are hardly differentiated from one another in form and function. There are small, skinny guys in both melee and ranged variants that die with one strike of a lighter attack. There are slower, larger versions of those same enemies that require one strike of the heavy attack to defeat. In other words, the only difference in approach is which button you’ll press in order to attack.

The remaining enemies are largely a variant of melee combat opponent where you’ll need to evade their attacks before striking at an opening. Be it the foe with what looks to be a hammer or the one that looks to have a sword, the player will be best served just running around, waiting for the enemy to complete their attack animation before swinging away once, twice, or thrice with a heavy attack combo. Once the damage has been dealt, start running around again in order to evade damage.

You’ll note that I did not recommend using the game’s actual dodge button. This is due to the absolute worthlessness of the move brought about by its distinct lack of invincibility frames. Yes, we’re discussing things with that sort of “hardcore” terminology! Nearly every action game worth its salt includes a period of invincibility during the character’s dodge attempt, balancing that temporary advantage by then including a recovery animation leaving the player vulnerable. Many games will also include the ability to “cancel” out of any action with a dodge, meaning you can stop mid-swing in order to evade an incoming attack.

Travis Strikes Again lacks both the invincibility frames and the cancel, meaning the titular hero will roll away at the exact same speed which he already runs. The only difference is that the dodge leaves him vulnerable for a moment, allowing enemies to close in and strike as Travis stands and recovers. It is more likely the player will get struck trying to dodge their opponent than simply running around in circles. The ability is useless.

It is for such reasons that the combat becomes relatively monotonous. Even if you were to switch up your abilities, the general strategy would be the same. Run around the enemy using the light or heavy attack when necessary, dodging their attack patterns until it’s time to use one of your special attacks. The shape each attack takes will allow the player to perform some limited degree of mix-and-match, but on the whole, no matter the foe and no matter the abilities, the approach is largely the same.

The level design is much the same. Each world has some form of unique feature, such as the second’s puzzle-like suburban neighborhoods whose streets you have to spin and rearrange in order to move forward. A later world is instead designed to resemble a two-dimensional side-scroller, complete with bouncing platforms to test and time jumps. Yet no matter what gimmick the level comes up with, the player is performing the same tasks each time. Move forward, kill little guys, then combat challenging foes in a locked-in arena.

It’s adequate gameplay in small doses, but each world demands a minimum of an hour from the player for completion. By time the player approaches a mid-boss, it feels like they should be fighting the boss of that level instead. Everything is at least twice as long as it ought to be, stretching already shallow ideas too thin.

Despite disagreeing with his assessment over the gameplay’s quality, I still recommend TheGamingBrit’s breakdown of the game.

Perhaps if Travis Strikes Again embraced those independent, arcade roots it seeks to honor and celebrate, crafting a trimmed down, two-to-three hour game that could be replayed frequently, it’d have managed better. That it chooses to instead linger unnecessarily is part of why I find the game so indulgent.

The rest of the indulgence lies purely in the story, a game whose intention to celebrate the industry instead feels a bit out of touch with itself. The game tosses lines out about player expectations, be it in regards to the power of mid-bosses, overly verbose dialogue, or even clapping itself on the back regarding the “good times” it has been providing for “the players”. It should be apparent that I did not share in these “good times”, feeling many of the game’s levels and fights to either be tedious or even frustrating. I did not enjoy this game nearly enough for Goichi Suda to be breaking the fourth wall, winking and nudging at me about what sort of a good time I was supposedly having.

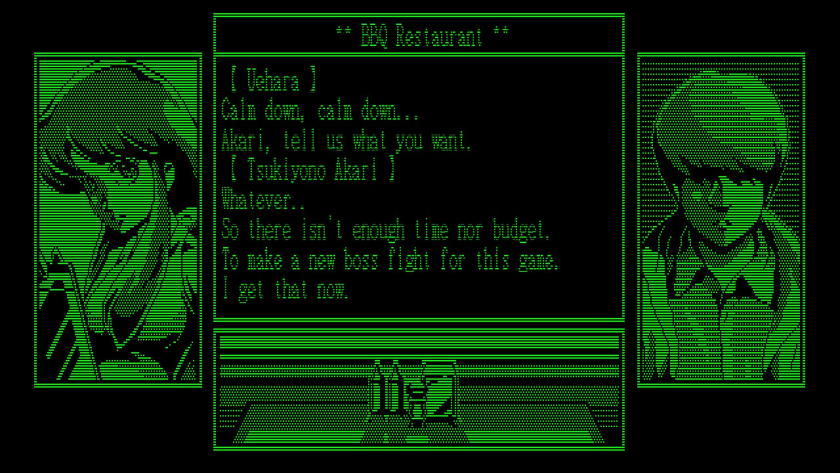

Ironically, the one aspect of the game I enjoyed most was perhaps the most verbose, lacking in any player agency at all. Between each game world the player is encouraged to hop on Travis’ bike and experience Travis Strikes Back, the low-res green-and-black DOS era visual novel. It becomes a bit absurd as the player reads descriptions and listens to 8-bit chiptune sound effects as Travis cuts through G-Men and assassins alike, all told to the player in a minimalistic fashion while waiting for the game to proceed to the next plot point. It is during these moments the game will look directly at the fourth wall, addressing the need for brevity lest the localization costs increase or the gamers become bored. At the same time, Goichi Suda has no problem detailing the meal Travis consumes at a diner, or making obvious the obscure game reference adorning the t-shirt of a fictional character. Perhaps Travis offering a compliment on such a character’s taste is representative of the fans Suda has encountered over the years at expos and conventions, bonding over mutual love for the unloved.

The moment which one fictional character complimented the other fictional character regarding taste was, perhaps, the moment where I realized just how indulgent Suda had become with this game. I want to give him some slack, however, because it is clear that such dialogue was written in an effort to connect himself with the love of his hobby again. To once more feel that zeal for the industry that he had when he was younger. It is why each game world harkens back to a different prior era of the industry, from the vector graphics of the 70’s and 80’s, to the awkward cinematic cut-scenes of the original PlayStation, a surprise inclusion of Suda’s ill-fated Shadows of the Damned, and even a cameo from Hotline Miami itself. The player is able to purchase t-shirts from a variety of other games, sporting independent titles such as Hollow Knight or SteamWorld Dig to larger titles like Dragon’s Dogma: Dark Arisen or The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask 3D.

For as Travis fights through one VR game after another, each lost to time, the player uncovers a personal journey of a game developer that had grown more frustrated with her inability to bring her visions to life. Combined with the real world knowledge of Goichi Suda struggling with publishers such as EA and Kadokawa Games, a picture is suddenly painted of a developer trying to drag himself out of the doldrums of development Hell and remember why he became a developer in the first place.

Taken on their own, these ideas are excellent. They are why I bought the game. Yet these ideas fail to emerge until the final half of the game, a point where I had already decided I’d only keep playing to see it through. Not out of enjoyment, and not out of a need to know what happens next. A desire to simply scratch it off the list.

In execution, Travis Strikes Again obscures this metaphorical biography with a screwball narrative about a game console secretly developed by the government to create some strange clone army of soldiers. Each world is prefaced by awkward fax messages and old school articles from fictional game magazines previewing these fictional VR titles on a fictional system. It is a stylish title whose least interactive visual novel narrative paints a picture of a fascinating yet awful alternate reality that I was enthused to know more about. It painted a picture of a better game I could be playing.

Instead, I was mashing buttons and proverbially checking my watch as I tore through each drawn out, tedious level. That I was able to finish it at all indicates that Travis Strikes Again isn’t a bad game. I even enjoyed brief moments of it. Yet that deeper meaning I dove in looking for was buried too far beneath the extraneous cruft of mediocre gameplay and self-indulgent drivel that I immediately uninstalled it upon completion.

This is one entry in the No More Heroes franchise I doubt I’ll ever play again.