Game Log Archive

Game Log is dedicated to the games I've been playing recently that encourage some degree of thought that I'd like to share. I cover games by their mechanics, narrative, and all other manner in which a game evokes emotion and engagement from the player.

Further study of Japan's economic situation provides a better understanding of just what it is that Persona 5 Royal is trying to address.

I had never heard of “The New Breed” until I read You Gotta Have Wa, the book by Robert Whiting that I referenced heavily in my prior write-up on Persona 5 Royal. Hiromitsu Ochiai was one of the baseball players detailed within the chapter, often outspoken against the traditional mentality of “fighting spirit” within the sport. He was a member of the shinjinrui, the “new breed” generation of young adults in the 80’s that were embracing individuality.

I could not help but wonder what happened to this generation, old enough now to be managing companies and even preparing for retirement. In 1988 the New York Times wrote that this “New Breed” favored forty-hour work weeks, vacation time, and the freedom to switch companies and careers over the excessive loyalty to one’s company – and therefore the excessive work hours spent – that their parents and grandparents bore. The affluent lifestyle of this generation – referred to as “Juppies” by the Chicago Tribune the same year as the Times article – more closely resembles that of a middle-to-upper-class American life than what one might expect of a Japanese.

So why is it that a modern piece of Japanese pop culture like Persona 5 Royal would represent older generations – those that would have been young adults of this “New Breed” in the 80’s – in a harsh light that favors all the old traditions they’d supposedly rebelled against? What happened to that “New Breed” and its desire for reasonable work hours and a comfortable lifestyle?

It turns out that it wasn’t just the affluent young adults that were gluttonously revelling in their excess. The entirety of Japan’s economy came crashing down in the early-to-mid 90’s due to irresponsible spending and poor investment, and the consequences are still being felt today.

The promising potential of a developer rediscovering his love of games is tarnished by the mediocrity of its gameplay and occasional self-indulgence in its narrative.

My interest in Travis Strikes Again diminished once its gameplay had been revealed. The preceding two titles of the No More Heroes franchise lack mechanical depth, but they possess a blistering pace of violence punctuated by bloody dismemberments and suplexes executed through simplified motion controls. A differently stylized version of DOOM’s Glory Kills, preceding one of the shooter’s defining features by almost a decade.

That stylish satisfaction looked to be missing in Travis Strikes Again, replaced by the top-down hack-and-slash antics more reminiscent of Gauntlet than the frenzy of Devil May Cry simplified. While I like to try and receive each type of game openly – even spin-off titles like Metroid Prime: Federation Force – the less hectic game style just had far less appeal to me.

It was only after seeing the thoughts and impressions of a few YouTubers I follow that my curiosity was once more piqued. Many on Twitter had observed Travis Strikes Again to potentially be game director Goichi Suda’s most personal work. TheGamingBrit’s deep dive on the game would push me towards a purchase. I became determined to see for myself what sort of auteur work was hidden within this low-budget follow-up to a game franchise forgotten by mainstream audiences.

What I found was certainly a personal work, but one whose most interesting content is tainted by the far more oppressive presence of mediocrity and self-indulgence.

Before diving into the narrative proper of Persona 5 Royal, let's examine the manner in which this game can give us a better understanding of how Japanese culture impacts its social dynamics.

Normally I don’t write about a game until I’ve finished it. This way I understand the full scope of its mechanics and gameplay as well as narrative. There are too many games that start out perfectly paced and exciting, garnering positive first impressions, only for the latter stages to fall apart from unreasonable challenges, glitched out levels, dragged out missions, or other disruptions to a previously enjoyable experience. A story’s themes may not fully emerge until its final hours, its true antagonist and their motivations kept hidden until the climactic finale. Or, like The Last of Us, the game’s entire narrative recontextualized by its conclusion.

I will not be doing that for Persona 5 Royal. The first hour of the game thoroughly pummels the player with the core of its thematic conflict, letting the player know that the struggle between young and old generations is at the game’s heart. By the thirtieth hour, it is not only examining this conflict in greater detail through its different characters, but it is beginning to ask questions of the perspective of “right” and “justice” that our heroes have chosen.

This is a game that has so much to dive into I may very well create a video on it some day. However, given my current rate of production in that regard, I’d rather not wait however many years until that opportunity arises. Instead I will be posting my thoughts as a series here on the blog, perhaps to be used as an outline for such a video in the future.

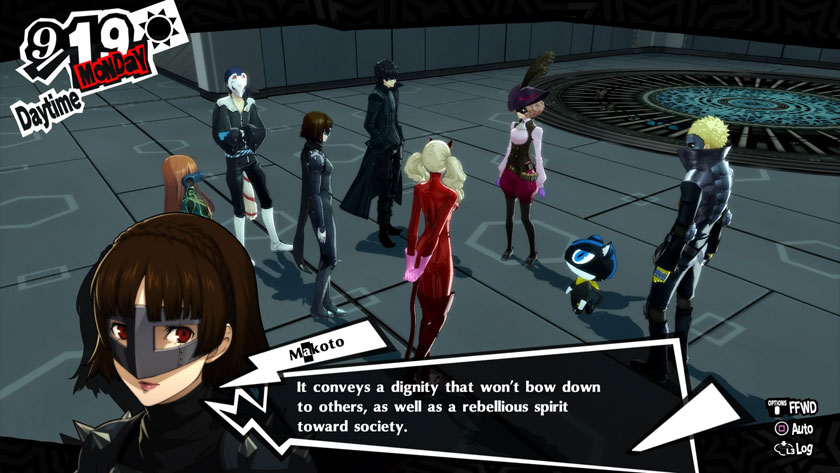

I don’t know for certain how many posts I will write, nor do I know what sort of subject matter each one shall focus on. There are individual characters whose situations could garner an entire essay themselves, such as Makoto Niijima or, in time, assistant to the heroes Mishima. There’s something to be said of the method in which our protagonists “steal hearts”, the wishy-washy nature of public opinion, and even the potentially inevitable failure of the rebellion and reform they seek.

Before I delve into any of those topics, however, I’d first like to establish the “plausibility” of the predicament our heroes find themselves in. Not their supernatural abilities, of course, but the very systems that cause them to feel trapped. The plausibility of, say, a sports coach being permitted to physically and even sexually abuse his own students.

To define a game's genre strictly through the mechanics it uses fails to understand the manner in which those mechanics combine to generate an emotional and mental response from the player.

My outrage to someone claiming a game is “like Dark Souls” just because it is difficult is about as predictable as the comparison itself. I never got far in either Demon or Dark Souls, and while I managed a few hours progress in Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice I found myself increasingly angry at the game’s many flaws. People had always described From Software’s design philosophy as “harsh but fair”, yet I found nothing fair in handicapping the player with a framerate of 30FPS while demanding such precision timing. The uncanny ability for enemies to pivot mid-animation, following your every movement regardless of their initial target, is the very definition of unfair. As a stealth game, Sekiro was fine. As an action game, it was a dominatrix demanding I lick the dirt from its stiletto heels and I’m sorry but masochism was never really my kink.

It was with some trepidation, then, that I acquiesced to my friend’s demands to try Bloodborne, From Software’s PlayStation 4 exclusive of the same “genre”. Like its brethren you’re expected to die almost immediately in order to learn a lesson about the cruelty of the world as well as death not being the end. Death does, however, come with a cost. Any of the precious currency used to gain levels and increase stats is lost. It’s possible to retrieve said currency, but should you die on the way back to your lost treasure or during retrieval, they will be lost permanently With few exceptions, all slain monsters and malcontents are only temporarily deceased. Any step into a sanctuary location immediately resurrects the defeated, meaning victory is fleeting.

It should be noted that I enjoyed games with similar mechanics. I absolutely loved Darksiders III once I had adjusted to the more threatening atmosphere, learning to “kite” or “aggro” enemies so that I could defeat them alone rather than in a group. Hollow Knight also drops all gained currency upon death, though with the added twist of reducing your total spiritual or magic power until you’ve defeated the dark spirit of your old corpse in combat. More recently I’ve played Star Wars: Jedi: Fallen Order which imitates the manner foes respawn into the world upon resting at a sanctuary.

It’s clear that I’m not completely opposed to certain mechanics found in From Software’s titles. In fact, should I play more of Bloodborne I may have more thoughts regarding why I’m so taken by it compared to the other titles. Yes, that’s right, I am indeed enjoying Bloodborne despite dropping the rest of the games with a deep sense of apathy or, in the case of Sekiro, absolute frustration. For now, however, I’d instead like to focus on the peculiar concept of “genre” and how it fails to illustrate the actual feel of a game. You see, yesterday morning, watching a crazed old lady jam a sickle into my character’s poor mutilated face repeatedly, I was struck by an epiphany:

Playing Bloodborne is a lot like playing a Resident Evil game.

It's a pretty good imitation, but that's all it is.

Rod Fergusson is clearly a man with a deep love for the Gears of War franchise. He quit his job as a producer with Microsoft Game Studios in order to join Epic Games and save the first entry of the franchise from a Hellish development. He had left to join Irrational Games to help ship Bioshock Infinite once Epic decided the third game would be their last. When Microsoft had purchased the rights to Gears of War, Fergusson rushed back in order to continue working on a franchise he loved.

Rebranding Black Tusk studios into Gears of War factory The Coalition meant entrusting the franchise to a team that had largely never worked on the franchise before. With this in mind, Fergusson had tasked the team with recreating individual combat arenas and set pieces from the first three games. He wanted the team to understand the franchise mechanics intimately: how the timing of waves and distance from an opponent could influence the feel of a skirmish. It was crucial for Ron that the team know what it meant to be a Gears of War game.

I believe this dedication is the sole reason Gears of War 4 was as competent as it was. The fundamentals of the franchise remain intact. However, I can’t help but feel as if I’d rather be fighting the Lambent again, a feeling I never expected to have.

There are depths to plumb in this seemingly simple and grisly visual novel about high school students trapped in a killing game.

It is not at all possible for the concept of wa or harmony to completely disappear in Japan. The disappearance of wa would mean that the Japanese would cease to be Japanese.

Masayuki Tamaki

This quote is used in the introduction of You Gotta Have Wa, a book written by Robert Whiting about the culture clash between America and Japan through the sport of baseball. It has been a fascinating read, adding further context and understanding to basic concepts I only knew of on a surface level: fighting spirit, honne and tatemae, and that of wa itself.

I enjoy reading about this stuff because it further enriches my perception of a lot of Japanese entertainment. Character decisions that otherwise seem foolish or baffling in an American context can be better understood when you know how the concept of “face” differs in Japan. I’m admittedly no sociologist, but ever since I began learning of these things I’ve better caught on to themes and ideas I otherwise would never have grasped in Japanese entertainment.

Which is why Danganronpa was such an enthralling game to play. On the surface it’s some twisted highschool murder game hosted by an unsettling robotic mascot bear. Its fur is divided between a white-and-cuddly half sporting an innocent smile while the vicious-and-black half bears sharp teeth and a fierce red eye. The contrasting halves represent the dueling concepts of hope and despair that serve as the story’s core.

It turns out that Gears of War 3 is not only better than I remember it being, but almost the best of the original trilogy. Too bad about the Lambent.

The Lambent are the worst aspect of Gears of War 3. I regretted selecting Hardcore difficulty as I slogged through the game’s opening chapters. “Do I really need to play this third entry before jumping into the fourth?” I asked myself. Did it truly matter? I knew the basics of the plot – who survived and who died – and I knew that Gears of War 4 introduced some new form of monstrous antagonist. Was it really worth suffering through the Lambent?

By the second or third hour into the game, shuffling through the trenches of a Locust stronghold, I was struck by a sudden realization: I was having fun. In fact, I was having more fun than I had at just about any point in Gears of War 2.

An hour later I found myself surrounded by Lambent once more. When the glowing, parasitic berserker showed up, I decided I had played enough and put the controller down.

For years I was certain Gears of War 3 had the worst campaign in the trilogy. It turns out the only thing I remembered were the worst parts. Playing all three games back-to-back, it’s clear that Gears of War 3 was almost the best campaign of them all.

What I once thought was the best Zelda game in years now feels like a victim of modern Nintendo design practices.

My response to A Link Between Worlds when it first released was unceasingly positive. Looking back at my initial write-up of the game, I had nothing but good things to say.

Which is why it’s so strange that I was not feeling nearly so warm about it on this recent playthrough.

Part of it may be due to having just played A Link to the Past before revisiting the 3DS sequel. I picked up the game again so that I might see where Nintendo took the concept some years later. If you watched my most recently released video, then you’ll know I spoke quite positively about that stormy, rain-drenched opening. It may honestly be my favorite opening of the entire franchise simply due to the tone it sets and the speed at which it gets the player into the middle of the action.

A Link Between Worlds opens with no such homage. It is far slower, taking cues from the latter Zelda games and their desire to establish a status quo before interrupting Hyrule’s peace. This means the same flaws that impact the “slow” or “easy” opening of A Link to the Past are made worse in A Link Between Worlds.

I don’t need every game to open up with action. However, I think some of the most memorable beginnings are those with a strong introductory gameplay segment. Final Fantasy VII has a classic opening not just because of the impressive 3D zoom-out and zoom-in of Midgar, but because the player is immediately hopping off of a train and fighting off enemy soldiers. Mega Man X begins on a highway with cars zooming away from the Maverick machines, pitting the player against monstrous helicopters that wreck the street in ways the prior games never tried.

Not to say that a calm, narrative-focused opening is always a problem. You simply need the writing chops to make it interesting, to invest the player in the experience enough that it will be worth revisiting on repeat playthroughs. Typically this is done by droppings bits of world-building that pay off later on, or hinting at later reveals that most players won’t think to be looking for on the first time through. A Link Between Worlds does no such thing. Its characters are shallow archetypes of every Zelda game, its twists hidden for the very end. While the colorful denizens of Hyrule certainly add some beneficial flavor to the game, they do little more than suck up time at the start as an obscene amount of text scrawls across the screen.

Really, though, what A Link Between Worlds attempts with story is a minor fraction of the experience. At most it made it harder to really get into the swing of things, the play sessions obnoxiously brief before I finally was able to sit down and feel invested in the game itself.

A look back at how a series had started strong only to be usurped by the search for bigger spectacle.

Gears of War is at its best when it is focused on simple skirmishes rather than major set-pieces. This is the conclusion I’ve come to after replaying the first two titles on my newly acquired Xbox One X. Graced with the limited edition of the console emblazoned with the franchise logo under a plastic facade of ice, I decided it would do me well to revisit the franchise from its origin before catching up on the next-gen exclusives I’d missed.

It was a decision that inadvertently left me feeling old as I reflected upon the timeframe these games originally released. My mind flashed back to more than a decade ago, playing the original game in my College apartment. As I explored the co-op campaign with an old Internet friend, we expressed our desire to see a Warhammer 40K style of game done with these shiny new cover mechanics. They seemed like such a revelation in 2006, delivering a stylized interpretation of the grit and lethality of war in a manner other first-person shooters had failed to achieve.

There was something raw about hugging against a crumbling wall or pile of sandbags, peering up long enough to deliver a volley of bullets into the subterranean cranium of a Locust soldier before ducking your head back down. As med kits were abandoned in favor of regenerating health, players were resorting to diving behind cover for a breather in all the other shooters anyway. Epic Games merely turned it into a mechanic. Walking around out of cover exposed the player to incredibly lethal doses of enemy fire. The environment of each battlefield was arranged so the player had to carefully consider their position, flanking opportunities, and avoidance of being flanked.

It’s too bad Epic began to chase the big, cinematic set piece moments like every other developer of the era.

Finding my own fun in Bungie's spaghetti mess of systems.

Going forward, Destiny 2’s post-launch game systems, features, and updates are being designed specifically to focus on and support players who want Destiny to be their hobby – the game they return to, and a game where friendships are made.

Luke Smith & Chris Barrett, Nov. 29th 2017 Bungie.net Community Update

Now we’re opening the door and saying, come on in, take a look around, if you like this place and want to make it your hobby, there’s a community here who’ll take you on new adventures.

David “Deej” Dague, Aug. 23rd 2019 interview with Eurogamer.net

If you’ve been reading this blog and following me for the past several years now, then you might recall my first critique of the original Destiny. My assertion at the time was that Bungie had built the experience as a culmination of all of their game modes and philosophies they’d developed into the Halo franchise. It guided the player from a basic and linear difficulty mode towards the more challenging content that tests the player’s quick-thinking and twitch-reflexes. The only thing I couldn’t wrap my head around was the grind.

As the years have progressed, I’ve felt an increasingly antagonistic relationship with the Destiny franchise due to the grind’s intentions clashing with what I want out of this hobby vaguely defined as “gaming”. My relation with this medium as an enthusiast drives me to play a variety of titles, to experience them repeatedly when possible, and to study the many genres that appeal to me.

Bungie wants you to play their game every week, several days of the week. They don’t care about other games. They want Destiny to be your hobby, not “gaming”.

The culmination of PlatinumGames' past work.

Astral Chain feels like the culmination of every major PlatinumGames action title that came before. It is not somehow larger in scale or more epic – its final boss is certainly a reversal of scale of Bayonetta’s escalation – but it implements small lessons and bits from just about every major entry prior.

This does not turn the game into something derivative, however. Whereas a licensed “Work-for-Hire” title like Transformers: Devastation felt like it was a barely modified variant of Bayonetta, Astral Chain feels unlike any other game out there. Of course, such a statement typically comes with hyperbole, as if to suggest that it’s going to blow your mind with how unique and revolutionary the game is. This statement is obviously untrue if it somehow carries influence from several other games from the studio.

The best way I can describe it is that Astral Chain certainly feels like an action game as you’d expect it to, but if you were to try and make direct correlations to any other big name in the genre – be they from PlatinumGames, Capcom, or one of the myriad smaller studios dabbling in the genre – you’d fail to find that one-to-one similarity. It is in this fashion that it feels unlike any other game, despite drawing from so many others.

Is a game made worse once you have seen through the formula of its gameplay loop?

I had devoted twenty-five hours of my life to Fire Emblem: Three Houses in fewer than five days, placing the temporal sacrifice upon the altar of simulated professorship and abstracted warfare. For those days I had felt a deep desire to dive back into the game, interacting with the different students across the artificial monastery and commanding young adults to battle. When I wasn’t playing Three Houses, I was thinking about it. It was like a hunger that no meal could adequately satisfy.

Then, a little over a week later, my stomach quieted. I wasn’t done with the game, but I certainly wasn’t enamored like I had been just days ago. “Ah, I’ll be doing this again,” I said to myself, beginning a new month where I once more chose to explore the monastery. Complete quests, interact with students and fellow faculty, then progress through each week’s instructions before launching into optional battles that further developed the game’s many characters. At month’s end I’d have a mandatory mission that would push the story forward. Combat was no longer challenging.

I felt as if, from a mechanical perspective, I’d seen all there was to see. The loop had become clear. I became aware of my status as the wagon wheel following the rut laid before me, plunging forward into a pre-established path rather than forging a new one.

A game that is hard to recommend despite its ambitious combat design and excellent writing.

My brain feels “disappointment” is an accurate descriptor of Caligula Effect: Overdose. My heart feels the term is too harsh, and would prefer to impress upon you the nature of the game as ambitious but flawed. On paper, it is one of the best games I’ve played in years. In execution, its greatest elements are outweighed by its most simple and tedious of design choices.

The last time I felt this way was with Akiba’s Beat, a game whose story struck me at a vulnerable point in my life and resonated in ways no other game in 2017 could. However, it’s dungeon-design was such that I developed a strong loathing towards the game and its repetitive, back-and-forth side-quests that endlessly recycled the same tiresome corridors without end. It was a pair of extreme reactions, with a deep love for the game despite a savage hatred for its flaws.

Only I don’t feel so extreme towards Caligula Effect: Overdose. I enjoyed its writing greatly, and it should have resonated with me deeply. For whatever reason, however, it did not. Perhaps because I’ve grown more accepting of my life and no longer dream the sort of escapist dreams I had in my youth. The game implemented a lot of the same flaws of dungeon design as Akiba’s Beat, but under most circumstances the combat was easier to avoid and thus dungeons easier to simply skip through. So while I did not enjoy the gameplay as much as any player would like from a game they purchased, it also did not frustrate me to the point of absolute loathing.

In the end, Caligula Effect exists in some Schrödinger state of recommendation. There’s enough neat ideas and excellent writing to be enjoyable, but the actual playing feels so lukewarm that I am woefully uncertain I’ll even remember having played it by year’s end.

Wherein I try to comprehend why I'm the only person failing to be hyped up for the most fan-demanded recreation.

When I say that the footage shown of Final Fantasy VII in Sony’s recent State of Play broadcast “isn’t my Final Fantasy VII”, I want you to understand that I do not say so with outrage or condemnation. It is simply the most succinct way I can understand my own feelings towards the new trailer. After all, there’s simply not enough information to determine what the end product will truly look like. I’m not even entirely certain how the combat is supposed to work. It’s too early to judge this product based on what little we’ve truly seen of it.

But then I see my Twitter timeline explode in hype and excitement and I can only wonder… why am I so apathetic? I had one mildly snarky comment regarding one perceived plot detail and nothing more. Yet everyone else is discussing not just how pretty the game is visually, but how well they’ve managed to recreate classic beasts while maintaining the atmosphere of each environment. From a visual perspective I should be at least somewhat impressed or excited.

To put it another way, even though I think the movie looks like it will have an average plot and even some painful gags, Detective Pikachu has me fired up because I simply can’t believe how good they made these creatures look in live-action. It’s not just nostalgia, it’s an opportunity to see this fantastic world I’ve only seen in video game and anime form brought to life in a way I never imagined possible.

Theoretically, the Final Fantasy VII trailer does the same thing. It takes childhood elements and breathes fresh new life into them with vibrant imagery… only, I’ve seen that sort of thing before.

Death is perhaps the most interesting horseman of the Darksiders series, and yet even he is not given as good a narrative as he deserves.

Snow soars past the panning camera towards frost-tipped mountains. Galloping through the ravines and climbing the pathways, the pale rider storms forth. Known to some as the Reaper, to others as Death, it is the name of Kinslayer that haunts him most. Death rides to not only save his horseman brother, but to perhaps assuage his soul. Maybe War’s salvation can make up for the murderous atrocity he had once committed against his nephilim brethren.

If you want to understand the basics of what makes a good character, look no further than the conflict Death must face versus that of War in Darksiders. That hulking, overly armored bladewielder battles enemies from without, but tussles none with demons within. Framed and betrayed, War’s entire journey is simply in learning who to aim his vengeance towards. Thoroughly epic and filled with the bloodlust that can only be quenched by tossing dice or mashing buttons on a controller, but hardly a resonant story.

Death rides in the guise of altruism, but it is the ghosts of his brothers long vanquished that haunt his soul. His journey is not to free his brother, but to instead free himself.

Unfortunately, the game has some trouble getting these ideas across.